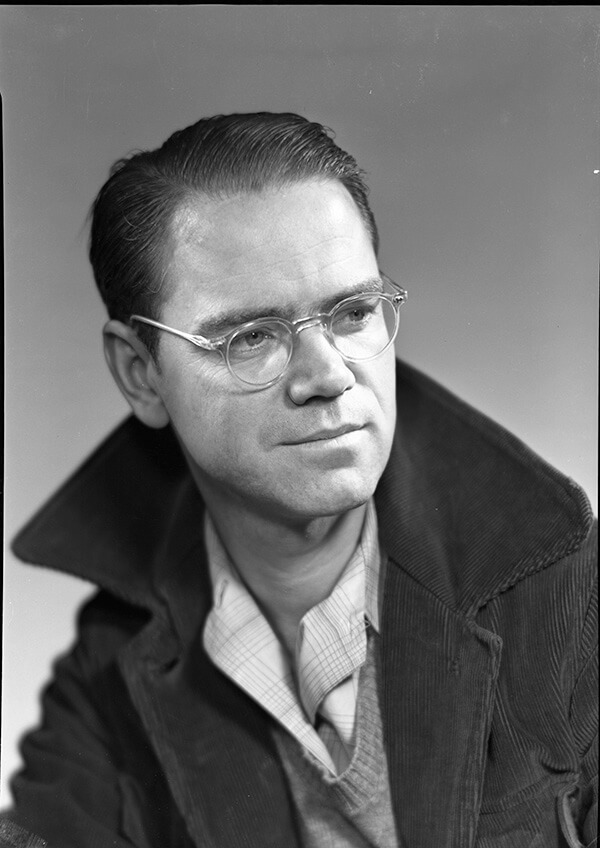

Earle Reynolds (1910-1998) grew up in show business, the son of trapeze artists. Despite a passion for the theater that never left him, he became an academic instead of an acrobat. He studied Anthropology at the University of Chicago and the University of Wisconsin. In 1943 he joined the research faculty of the Fels Institute for the Study of Human Development, established on the campus of Antioch College in 1930, chairing its Physical Growth Dept. There he produced a range of papers on skeletal development in children and wrote a number of stage plays on the side. Yellow Springs was fertile ground for a playwright in the 1940s and several of his works were staged by Antioch Area Theater, a production company formed by the College’s Dept. of Dramatics, some to critical acclaim.

He first went to Japan in 1951 as a researcher for the Atomic Energy Commission to study the effects of radiation on children that had survived the atomic bombs detonated over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Horrified by the results he had found, Earle realized the dangers that nuclear technology posed to all humanity earlier than many other scientists, and that atomic weapons should simply be done away with.

Reynolds had yet to become the anti-nuclear activist whose exploits gained him international fame and notoriety; he would try his hand at shipwright and sailor first. In the 1950s he built his own sailing vessel, The Phoenix, and from 1954 to 1958 the Reynolds family was at sea circumnavigating the globe. In Hawaii they met the crew of the Golden Rule, Quaker activists then on trial for planning to sail their vessel into an atomic test site in the Marshall Islands. As a result Phoenix would go where they no longer could, becoming a latter day Samuel Prescott to the Golden Rule’s Paul Revere by completing an historic ride cut short by the authorities.

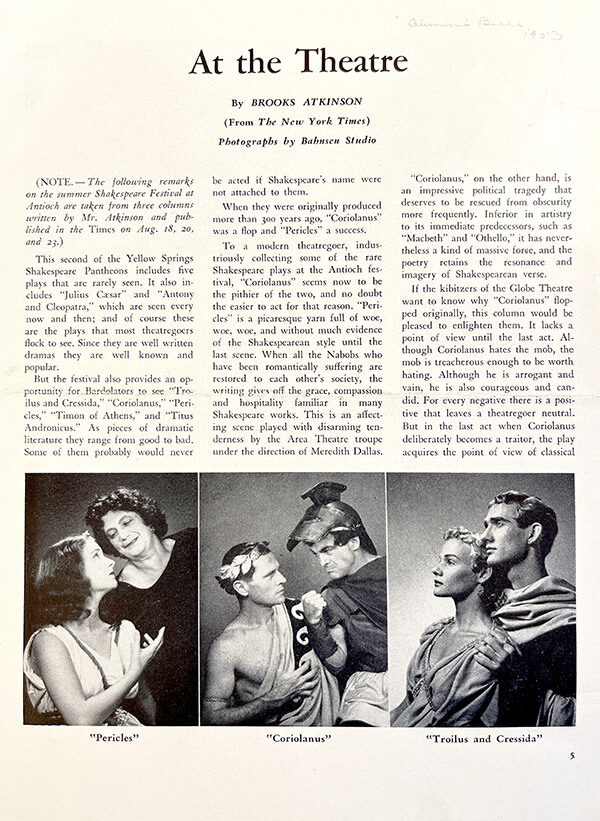

Amid the cascade of international news coverage of Reynolds’ exploits was the brief notice reprinted here from a very likely publication, The New York Times, though authored by perhaps its unlikeliest writer, Pulitzer Prize winning theater critic Brooks Atkinson. Known as the most important reviewer of his time, Atkinson could make or break a Broadway production with his column. While a discussion of international politics and atomic weaponry might seem beyond his realm, Atkinson had been a war correspondent in China during World War II and won his Pulitzer while on assignment in Moscow before returning to his theater desk, so he knew something of the Far East and the issues of the world beyond the stage. He also knew something of Antioch College and the Village of Yellow Springs, Ohio, having reviewed most if not all the productions of William Shakespeare famously conducted outdoors on a stage constructed on the steps of historic Antioch Hall in the early 1950s. From his conclusion, one wonders if Atkinson had even seen one of Earle Reynolds’ own plays, and perhaps he had liked it enough to retain interest in Earle’s subsequent good works.

Critic At Large

Scientist Sailed Into Nuclear Test Area With His Conscience At The Tiller

By BROOKS ATKINSON

After two and one-half years of struggling with the conscience of an American scientist, the United States of America has given a little.

On Dec. 29 the United States Court of Appeals in San Francisco reverted the conviction of Dr. Earle L. Reynolds for violating the Atomic Energy Commission’s regulations that forbade entrance into nuclear testing areas around Eniwetok. In June 1958, Dr. Reynolds, his wife, daughter and son and a Japanese citizen deliberately sailed his ketch, the Phoenix, into the restricted area to protest the testing of nuclear bombs and specifically the legality of the A.E.C.’s authority.

As he expected, he was arrested at sea by the Coast Guard when he was sixty-five miles inside the area. A court in Honolulu sentenced him to two years in jail, the last six months to be suspended.

Although the Court of Appeals in San Francisco has ruled Dr. Reynolds’ conviction improper under the statute cited by the lower court, it adds that he can be tried for “trespass,” which is a misdemeanor and not a felony. Now the United States of America will have to decide whether or not to begin again at the beginning. The Eniwetok area is still restricted by the Navy, but not the A.E.C.

Until the spring of 1958, Dr. Reynolds, an anthropologist, had been, he now thinks, rather derelict as a citizen. He had never taken much interest in politics or causes. At that time he and his family happened to be in Honolulu on their way back to Hiroshima, Japan, to complete their circumnavigation of the world in his 50 foot ketch. This had been a sentimental venture. When he was a youth his imagination had been fired by reading Capt. Joshua Slocum’s story about his circumnavigation in the sloop Spray. Although Dr. Reynolds had never been at sea in a small ship and knew nothing about celestial navigation, he had always wanted to emulate Captain Slocum. Beginning in 1954 he did.

When he got back to Honolulu in 1958 after a happy experience, the four members of the crew of the Golden Rule (three of them members of the Society of Friends) were being tried for proposing to sail into the Eniwetok restricted zone. Dr. Reynolds had never been in a courtroom before. But the trial of the crew of the Golden Rule engrossed him more and more because it involved something he had strong convictions about.

Before sailing around the world he had studied the effects of radiation on children at Hiroshima as a representative of the National Academy of Science. He had been appalled, and still was, by what his research taught him. The more he thought about the court trial the more he was convinced that the crew of the Golden Rule was right and the Government wrong.

It seemed to him that he ought to complete the mission of the Golden Rule by sailing his ketch into the restricted zone. It was a decision of conscience, involving risks that rather frightened him; but his family and the Japanese crewmen agreed with him. Before he got underway he notified the appropriate government agencies of his intentions. That’s how it all happened.

At present, Dr. Reynolds and his family are living on their ketch in Hiroshima, where he is completing a year’s appointment as guest Professor of Anthropology at Hiroshima Jo Gaikun, a women’s college sponsored by the Methodist Board of Missions. So far his legal expenses have been about $25,000, almost entirely met by voluntary contributions from about 5,000 individuals.

“Since there was no organization behind me and I was not backed by any group,” he told Robert Trumbull, correspondent of the New York Times in Japan, last week. “I was considerably amazed by the response of the American people. It reconfirms my faith in Americans as a people.”

As for a Jail sentence, he said:

“We have been prepared all along for the possibility of my having to go to jail. Our plans were laid out in terms of this possibility.”

Concerning the testing of nuclear weapons, he said:

“The moral question is the simplest. While the mass killing of civilians may be justified under the laws of war or from a military or political point of view, it cannot be justified morally.”

Fifteen years ago, when he was living in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Dr. Reynolds wrote a play entitled “I Weep For You.” Quite a good title.

New York Times

January 10, 1961