In the Summer of 1861 the Mann Memorial Committee decided that sculptor Emma Stebbins would create the bronze statue of Horace Mann for the grounds of the Massachusetts Statehouse in Boston. Four  years later, with the statue a month from its dedication on the Fourth of July, his widow Mary wrote the following letter to Senator Charles Sumner. A gigantic figure of his time, Sumner was a leading member of the political faction known as the Radical Republicans, who made certain that the goal of the US Civil War was the destruction of slavery, pushed hard to ensure that the Fourteenth Amendment passed, started impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson, and enforced the most punitive Reconstruction policies that they could upon the former Confederacy.

years later, with the statue a month from its dedication on the Fourth of July, his widow Mary wrote the following letter to Senator Charles Sumner. A gigantic figure of his time, Sumner was a leading member of the political faction known as the Radical Republicans, who made certain that the goal of the US Civil War was the destruction of slavery, pushed hard to ensure that the Fourteenth Amendment passed, started impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson, and enforced the most punitive Reconstruction policies that they could upon the former Confederacy.

Only a personality with the force of Sumner’s could stay at the head of such a strong willed faction. From the moment he entered the Senate in 1851, Sumner attacked the slave interests with the blistering oratory that had made him a public figure when he was still in his twenties. In 1856, he delivered his famous “Bleeding Kansas” speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, excoriating its architect Andrew Butler (D-SC) and his love for “the harlot, slavery.” Two days later, Butler’s cousin and Democratic Representative of South Carolina Preston Brooks redressed the insult with his cane, beating Sumner nearly to death as he sat at his Senate desk. He survived and served until his death in office in 1874.

Though permanently diminished by the assault, Sumner remained at the forefront of government as well as its most courageous champion for civil rights the rest of his life. He also continued to be a much sought-after public speaker, such as he is about to do at time Mary wrote this letter, the original of which resides at the Library of Congress (Antiochiana has a facsimile copy known as a “photostat”). Mary refers to Sumner doing “justice to Mr. Lincoln” in the eulogy he is scheduled to deliver in two days time. Entitled “The Promises of the Declaration of Independence,” Sumner’s address came in at just under 17,000 words, so if “justice” was not done surely the people of Boston got their money’s worth that day. She then makes reference to her “little book,” first of the five volumes of Life and Works of Horace Mann, so hardly little at all.

Mary seems to not care too much about her late husband’s statue or for its artist. Years earlier she had expressed her desire that a man named Ball Hughes should do the work, and perhaps she’s still disappointed he wasn’t selected. That she told Stebbins that a good statue would “be a miracle” seems thoughtless if not directly unkind, and her reference to “genius” makes no supposition that the artist actually possesses any at all. To interpret this apparently dismissive comment another way, her last paragraph says she is proud of her country for the first time in her life, and maybe she is simply too overwhelmed by the fact that slavery had finally become illegal to give thought to such earthly concerns.

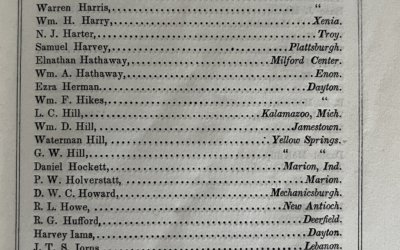

Photo: Carte de visite of Senator Charles Sumner by Alexander Gardner. Matthew Brady Studio

Concord, May 30th 1865

My Dear Mr. Sumner,

I have just learned thro’ the papers, for I have no other notice of the fact, that the statue of my husband has arrived in Boston, and that it will soon be set in its place. If any of the gentlemen interested in the matter ask you to speak any words upon the occasion, I hope you will consent, for I think no one would do so much justice to him in all respects. I am jealous of sons of those Boston men who in hard times flinched from their friendship to him. You will feel and know that no man who has passed from our sight would so deeply (one line masked in photostat) over our land. I do not know whether you will do justice to Mr. Lincoln – if you do, so much the more precious will your tribute to him be – but I think you fully realised my husband’s interest in human freedom.

A few days since I read the last proof sheets of my memoir. It is a singular coincidence that the two things should happen at once – the arrival of the statue and the issue of my little book. I know how inadequate it is as a memoir, but my chief object was to let him speak for himself. I have written enough about him to fill volumes but this is all they would print. It will be pleasant to me to have (one line masked in photostat) hands, who knew so well the motives that actuated him – and after all it is a man’s motives that make the man.

It will be a miracle to me if Miss Stebbins statue is good, as I told the dear lady herself, but there is no knowing what genius may do.

Let me here rejoice with you that your labors have been so crowned with success. How my husband would have loved to work with you – but if the spirits of the departed ever aid their earthly brethren, he has kept watch and ward with you, strengthened you when you needed strength, sustained you in the dark hours, & poured the wine of triumph into your cup of joy when all was achieved. And he will continue to uphold you in the work yet to be done. I tremble for the next step, but if God spares you for another Congress, I shall not be without hope and even faith that the crowning glory will be given to what has already been done, and that we shall indeed be a nation of freemen enjoying equal rights before the law. For the first time I am proud of my country, & if this last great event has not compacted us into a nation of moral heroes, nothing can. I hope you are not to pronounce a requiem, but only a benediction, for surely Mr. Lincoln passed from life to Life at just the right moment.

With great regard,

Mary Mann

“Songs From the Stacks” is a regular selection from Antiochiana: the Antioch College archives by College Archivist Scott Sanders.