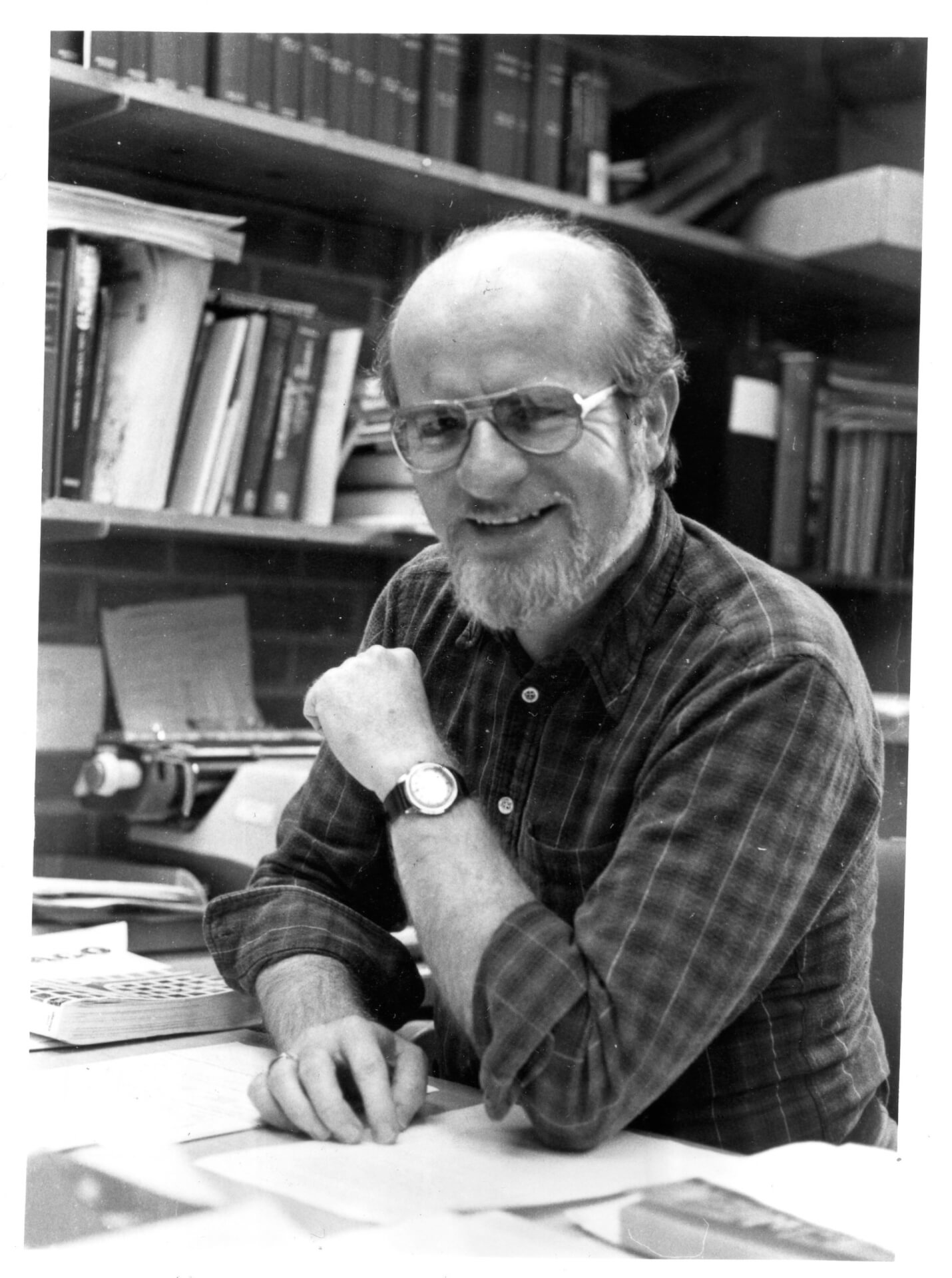

Bob Fogarty having a laugh in his book strewn office

Community Creativity and Commemoration: Remarks by RS Fogarty

by Scott Sanders, Archivist at Antioch College.

Antioch College lost a shining academic star when Robert Stephen Fogarty died in August 2021. Having retired from teaching in 2004 and editing The Antioch Review since 1977, it’s easy to lose sight of what a great historian he was. A renowned scholar of American intellectual and social history, Bob focused on utopian societies, most notably the free love Oneida Community in New York, producing seven books. He taught American History at the College for over 30 years as well as, as he used to say, “one-fifth literature” just like his predecessor, Louis Filler. Over his long teaching career, Fogarty inspired many Antiochians to pursue history as a field of study, producing several PhDs.

At the 2004 Alumni Reunion, Fogarty’s former students honored him with a program called “Community, Creativity, and Commemoration.” The speakers for the event were Steve Benowitz (‘71), Laura Camozzi Berry (‘82), Larry Foster (‘70), Betsy Jameson (‘70), Lester Lee (‘72), Catherine McHugh (‘73) , and Kim McQuaid (‘70). They came to share stories about being in his classes and how he influenced them. Among the plaudits heard that day were “Through him, I learned to think more critically, write better, and have a deeper appreciation for opposing points of view;” “He gave a shape and a spur to my thinking that it had never had before I met him, and it is the thing I have tried to emulate my entire teaching life;” “If Bob Fogarty has significantly influenced my own scholarship, that impact is minor when set against the impact that he has had on the development of modern communitarian and utopian scholarship as a whole;” “I think he always got to the points he thought were important, but he let us think we’d taken him there;” “He wasn’t inviting us to study something messy…with the expectation that it would become clear; He was inviting us to study something messy with the expectation that it was likely to remain messy;” “Bob, not to put too fine a point on it, had a lot of guts”

Following the aforementioned luminaries was Fogarty himself. His remarks, full of the wit and candor that helped make him a great teacher, are reprinted below.

*****************************

One of the first things that a historian learns is to distinguish between a fact, an opinion, and an interpretation. Your interpretations of my impact on your careers and lives made me blush at times. But the eloquence with which you all delivered your remarks made me proud. Not to mention the good humor you all still possess given the fact that you graduated from this humor-challenged institution. I have survived Antioch in part because I have been able to keep my humor intact while it was deadly serious about silly matters. That the omphalos of the world was located in a small town in Ohio surrounded by pigs and corn struck me as a cosmic joke, particularly in light of the fact that its most inventive president, Arthur Morgan had, as his favorite beverage, a cup of hot water.

When I first arrived here in the summer of 1968 there were several things that struck me: one, that the buildings were capable of being levitated by the amount of marijuana in the air; two, that the faculty was, by and large, quite capable, varied and feisty and the students were remarkably bright and responsive. I have dined out on stories about Antioch for my entire career and these were tales straight out of Ripley’s Believe It or Not. One of my favorites was an incident that took place in the early seventies in a class on “American Urban History.” I was-as usual-scribbling something on the blackboard (like a series of numbers “4142334425059125” that indicate the stations on the “F” train in New York-urban iconography) or drawing a map of the United States that resembled a side of beef when a student-obviously in the middle of a psychotic break- came into the tightly packed classroom on the third floor of the Main Building where the history department held sway.

Antioch Record Sep 1972: The only known photograph of Bob Fogarty in shorts.

The distressed student began to mimic my style by pointing to the class and repeating what I said. I turned to him and asked that he leave the classroom and then I turned to the class and asked how many of them wanted him to stay. The class remained silent and not a single hand went up in the class of about 35. At that point in Antioch’s history, just about every student had had a job working in some mental health facility or had worked with troubled people in some kind of setting. It would have been easy for some psychology or sociology majors (and there were plenty of them) to side with their fellow student (they had all read Goffman and Szasz), but they understood that things could get out of hand. The student who was having the psychotic break had not, however, lost all of his wits and had obviously been to a large number of political meetings. He quickly turned to me and demanded that I hold a secret ballot. With that, I took him by the arm, led him out into the hall, and found a Dean of Students to take care of him. Even in his distressed state, he indicated a quickness of mind that was not uncommon in those heady days.

The students had acted responsibly and it was because of their co-op experience that led them to act in a manner to protect the sanctity of the classroom and the sanity of their professor. It was not always the case, but the history students were as a group bright, hard-working and rigorous. During the lockout/strike of 1973, they all finished their senior projects under ghastly conditions (classes were held off-campus and the college was shut down for nine weeks while the administration “negotiated” with the strikers) and the history faculty (Hannah Goldberg, Frank Wong, Mike Kraus) all continued to teach and try to keep the students engaged as Catherine McHugh has indicated.

When I became editor of The Antioch Review in 1977 things began to change slightly as I divided my time between history and the magazine, which has had its own tumultuous history (another series of stories). But there were a number of talented students who worked for me as interns at the Review (like Laura Camozzi Berry). Throughout all these years I have been blessed to have solid colleagues (like Fred Hoxie and Barbara Davis) who took their own teaching seriously, required students to read primary sources, and respected their students.

One of the things that I learned at Antioch was that it was essential to respect students, to treat them as individuals (not some prototypical “Antiochian”), and to suggest that doing research was actually fun and that reading and writing were noble activities that brought great rewards. There is a great deal of ‘can’t’ uttered about education and Antioch has had its fair share of cant-makers. Phrases like “innovation,” “change agents,” “students and faculty as co-learners” and currently “learning communities” (when was a serious college not one) trip off the tongues of administrators who fail to understand that the heart of an Antioch education can be found in the prophetic Book of Daniel where it says that “many shall run to and fro and knowledge shall increase.” Kim McQuaid, an indefatigable researcher, and author, knows this better than anyone else since he helped me research an article for the Review on Change Magazine titled “A Nice Piece of Change.”

There was always talk about the “real world” (meaning anything that happened outside of Antioch) but many students (certainly the ones who spoke here) appreciated that the life of the mind was as real as anything else and certainly more real than, say, politics.

I have been fortunate to continue to have contact with many of my former students in part because I wanted to and because of the close bonds established between a teacher and a student, particularly if you supervise a hundred-page senior project. I share a birth date with Lester Lee, see Susan Guerrero (now with the New York Times) and George Judson (now with the San Francisco Chronicle) when I am in their cities, shared meals with Steve Benowitz when he was in Washington (and hope to continue that tradition after his move to Seattle), talk about professional concerns with Larry Foster and Betsey Jameson and have run into innumerable students in unlikely places like Mont-Saint-Michel or in London.

There I had a chance encounter with a particularly difficult student who had a brooding presence about him and would suddenly appear on my doorstep when I was talking with a colleague. He was so asocial that the co-op department had difficulty placing him on a job. On his first visit to discuss his senior project, he announced that he had already come to his conclusions about his topic. I reminded him that it was usually the other way around. First, you do the research and then you come to the conclusions. But I knew I was in for trouble.

As some of you know I have spent a great deal of time in London and Oxford over the years working on various projects. London is a city that I love and know well and I was startled to see this self-same brooding student at the other end of a train on the London underground several years after he graduated. There he was in the same car and as he approached me he asked in his characteristic backward manner: “What are you doing here?” He presumed that I was out of place (and may have been) given his own state of mind. I immediately got off at the next stop and fortunately, I have yet to see him again. But you never know given the way some Antiochians get around.

Finally, I want to say that my thirty-five years of teaching at Antioch have been rewarding because of the relationships that I have developed with students like the ones you have heard today. They are all accomplished in their own fields from finance to teaching to administration; all inventive about the work they do; and all generous with their time and talents. These are the kinds of individuals who create a reputation for a college by their own independence, by their good humor, and by the way that they live their lives.