By Scott Sanders, Antioch College Archivist

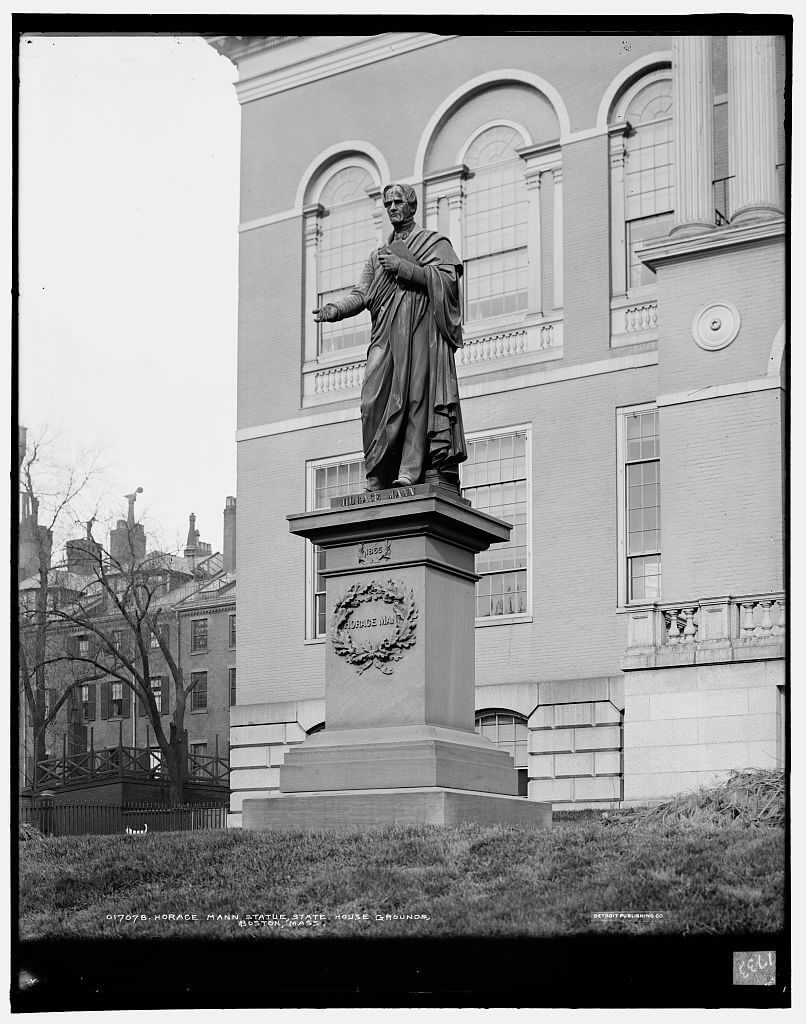

The first casting of Stebbins’ Mann statue at the Massachusetts Statehouse in Boston.

The statue of Horace Mann, first president of Antioch College, was erected in 1936 on a site in Glen Helen that was once part of Mann’s farm by Hugh Taylor Birch, class of 1869, as part of a national celebration marking the centennial of public education in America. The statue is the second of two cast from the same mold, albeit about 75 years apart, and one of the few bronze works of its sculptor, Emma Stebbins, who normally worked in marble.

A movement to construct a statue to honor Mann’s accomplishments began in Boston shortly after his death in 1859. One impetus that gave momentum to this effort, led by Mann’s widow Mary and her sister Elizabeth Peabody, was a statue erected that year outside the Massachusetts statehouse to honor another favorite son: Senator Daniel Webster, whom Mann had once admired but the two became bitter rivals over Webster’s support of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Many a Mann supporter agreed that Webster had sold his Whig principles to slavery, and therefore sought to have a statue to honor a representative of their state who did not compromise the fundamental belief in equality merely to sustain the unsustainable relationship between the States. Mann’s friends and family began to raise money almost immediately and proceeded to find a reputable sculptor, which they found in Emma Stebbins.

Stebbins (1815-1882) came from New York City, a product of wealth and privilege. Her brother Henry made a fortune on Wall Street, established the brokerage firm of HG Stebbins & Son, served several terms as president of the New York Stock Exchange and a stint in Congress, and was a prominent enough New Yorker that he was appointed president of the commission that established Central Park in 1857. With such resources at her family’s disposal, Emma had access to the best possible art education, and she studied in Italy with Welsh Neoclassical sculptor John Gibson. In addition, she studied anatomy, as did most of the Neoclassicists, in order to more perfectly duplicate the human form.

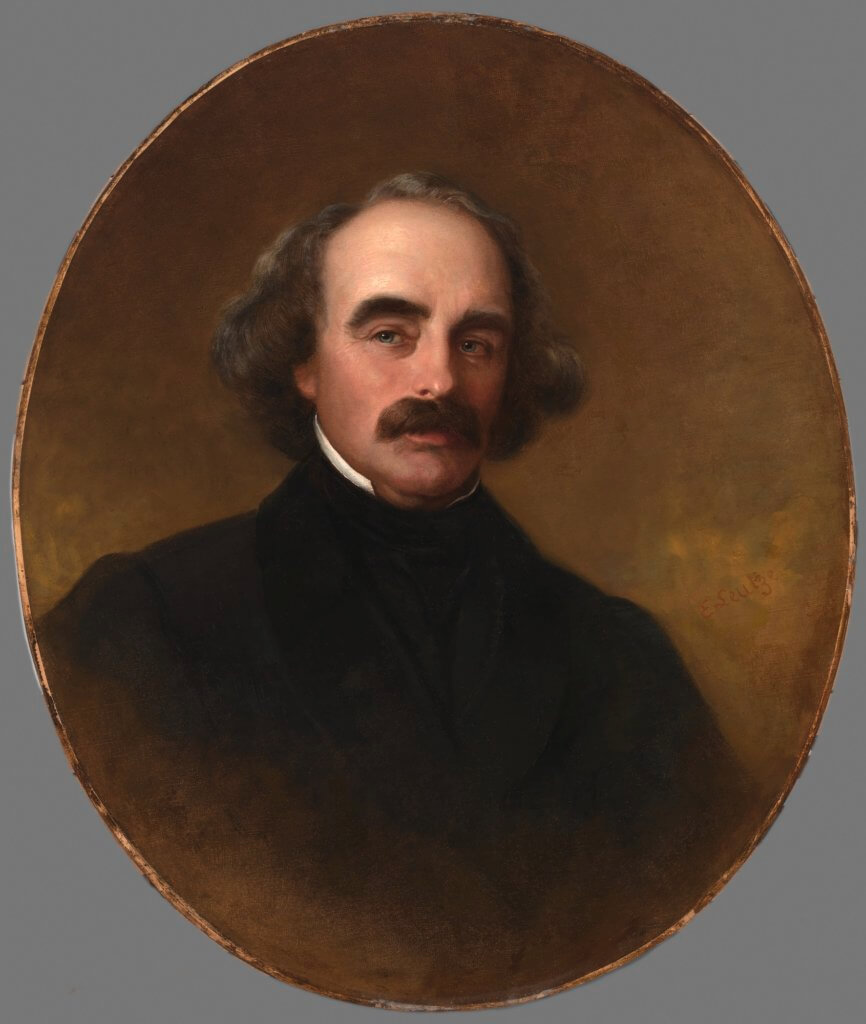

In the summer of 1861 Emma wrote a quick note to Nathaniel Hawthorne, reprinted below, who by then had returned from his Consulship in England and was residing at his home “The Wayside” in Concord, MA, previously the home of Bronson Alcott and today part of Minute Man Historical Park. It is the only communication from the sculptor in collections of Antiochiana. Her comment on “the strange and new aspect of affairs” in Southern Italy might possibly refer to the latest developments in the Wars of Italian Unification: Garibaldi’s forces had recently concluded a siege of the city of Gaeta, considered an early turning point in the Risorgimento. While the relevant information on the statue appears in the postscript, the two people mentioned in the body of the letter deserve explanation: Mrs. Blodget of Liverpool ran a boarding house where the Hawthornes stayed two weeks before heading home, and Miss Cushman, the love of Emma’s life. Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876) was one of the most famous actors of her time, known for her brilliant performances of Lady Macbeth as well as Hamlet and Romeo, the latter played opposite Charlotte’s sister, Susan, who played Juliet. Cushman was equally famous for her many romances with other women, including Emma, whom she met while living among expatriate American women artists in Italy, a group described by Henry James as the “White Marmorean Flock.”

Sculptor Emma Stebbins with Charlotte Cushman.

Emma’s postscript reveals her highly detailed approach to her art with the mention of “a cast of Mr. Mann’s head taken by Fowler from life.” This is undoubtedly Mann’s longtime phrenological friend, Orson Squire Fowler, the greatest popularizer of the pseudoscience in America, and plaster casts of prominent figures’ heads was a common method of study. Note Emma’s interest in obtaining as much information as possible about Mann’s life, “especially his connection with Antioch College,” a connection considered by many of his Eastern friends to be at best the anticlimactic end to his productive life. How these details end up as part of the Mann statue is not clear, though as part of her study Stebbins has already read Mann’s “splendid,” monumental Inaugural Address of over 20,000 words, which had been published in 1854.

Balte June 29./61

Dear Mr. Hawthorne,

Your note was forwarded to me from Boston, & I received it just as I was on the point of starting on a little southern excursion—to see with my own eyes before leaving the country—something of the strange and new aspect of affairs—At our first stopping place I hasten to acknowledge its reception and to thank you most earnestly for your kindness in writing it.

I shall probably stop at Mrs Blodget’s in Liverpool—and it will gratify me to be the bearer of anything that you or Mrs. Hawthorne may wish to send—We expect to remain in Liverpool a week or two—& then go on to London—If it should be of importance to have your letters immediately forwarded I will endeavor to do so—or if time has no consequence, will keep them until I go to London myself. Miss Cushman will be in Boston next week—at No. 70 Pinckney St. & anything sent to her will reach me safely.

With best remembrance to Mrs Hawthorne Mrs Mann and Miss Peabody—and many thanks for your kind appreciation of my work—I am with the highest esteem & regard—

Faithfully yours

Emma Stebbins

Will you be so good as to tell Mrs. Mann, that there is a cast of Mr Mann’s head taken by Fowler from life—the prehead & mouth & chin are good as compared with the photograph—there are the usual defects inseparable from this method of taking the cast—but it will be very useful for the anatomy which cannot alter—I should be glad if she will let me know—where I can find the best memoir of Mr Mann covering all his life & especially his connection with Antioch College—Tell her I think the Inaugural Address was splendid.—

Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1862. Portrait by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze