by Scott Sanders, Antiochiana.

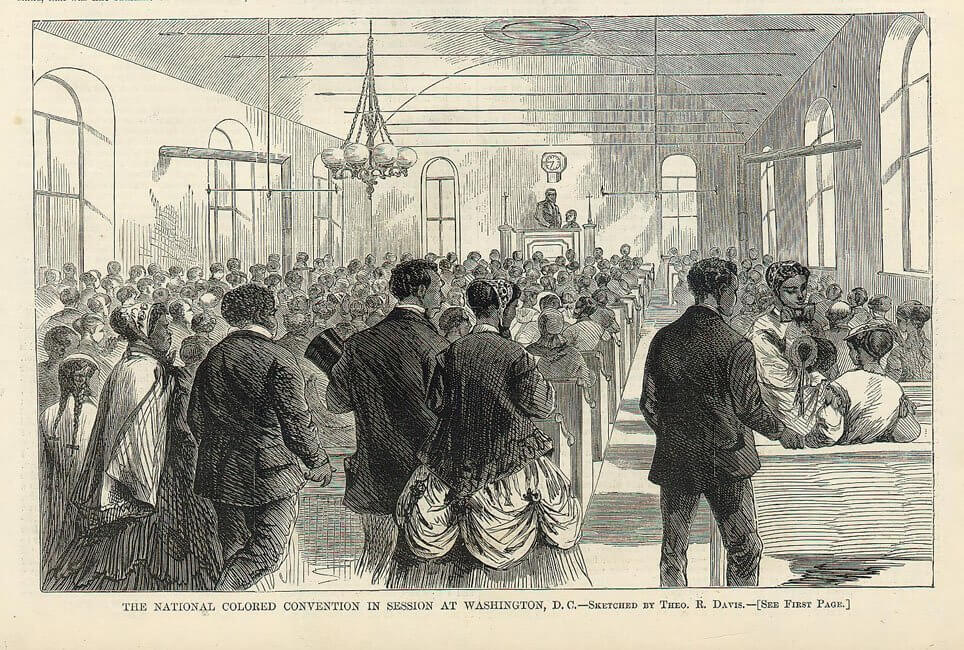

State and National Colored Conventions were held from the 1840s to the 1890s. This illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicts the National Colored Convention in Session at Washington, D.C, 1869.

In January 1852, an organization called the Colored Freemen of Ohio met at a convention in Cincinnati to decide the question posed most notably by Lenin, “What Is To Be Done?” It was just the latest in a series of Colored Conventions going back to 1830, in which black civic leaders discussed a whole host of issues relating to the future prospects of African Americans, and how to deal with them. Chief among a host of issues was the burgeoning “Colonization Movement,” an effort to “repatriate” free blacks to Africa, behind which there were many motivations. Led by the American Colonization Society, some of its adherents were abolitionists who felt that freemen would never gain real equality in the US, while others came from a distinctly proslavery perspective, seeing free blacks as fuel for their greatest fear: slave rebellion.

The Colored Conventions almost unanimously opposed colonization. The Cincinnati meeting, held at Union Baptist Church (the oldest black congregation in the city), roundly condemned it a “wicked system” and resolved their opposition “soul and body to the African Colonization scheme.” Number 26 of over thirty resolutions passed at the convention states that opposition most emphatically: “That we claim our rights at the hands of this government, not only because we are native born American citizens, but because our ancestors and ourselves have contributed to the wealth, honor, liberty, prosperity and independence.” Many present and their ancestors had undoubtedly made those contributions as slaves as well as citizens, and they weren’t about to give up their stake a nation they’d helped to build.

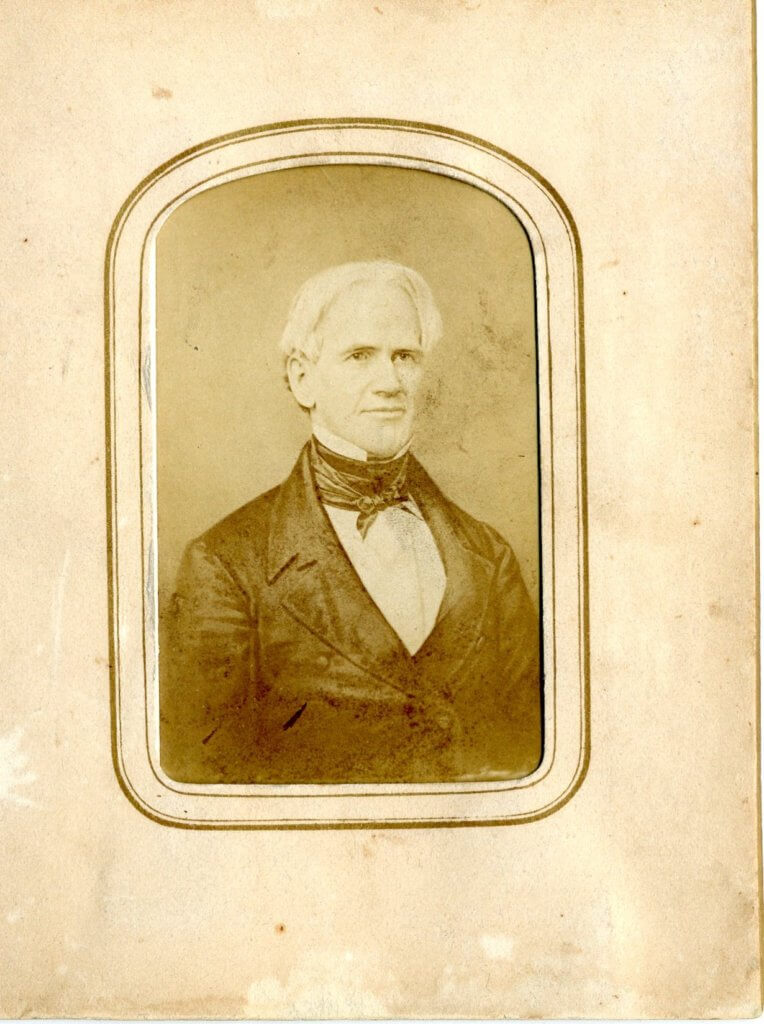

Letters solicited from prominent men of an antislavery outlook were read at the Convention, including one from Horace Mann, Whig representative to Congress of Massachusetts and not yet the first president of Antioch College. They were asked to share their views on the future of African Americans as Americans, and true to his most verbose form, Mann’s was the longest one contributed, described in the minutes as “able, argumentative, and full of advice.”

The minutes also say that the letter, which was read aloud to the delegates, was “received with a round of applause.” Nonetheless, Mann took some heat for it. Drawing no doubt upon his own classical education, not to mention the latest scientific inquiry, much of what he says would now be characterized as scientific racism. Based on a host of social evolution theories more anthropological than biological, practically any of the works Mann might have read on race would have been thoroughly Eurocentric, and pseudoscientific at best by modern standards. To learn more about the history of the Colored Conventions, visit the Colored Conventions Project online at https://coloredconventions.org/.

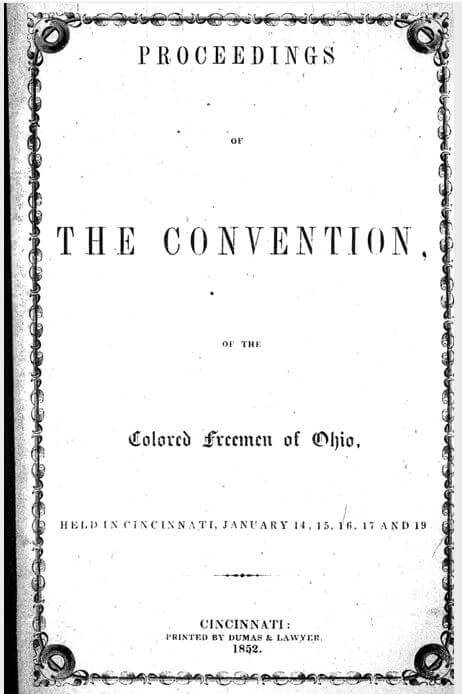

Cover page to the published minutes of the convention held in Cincinnati in 1852.

Mann to Theodore Parker: The enclosed correspondence explains itself, as they say; only that my letter is so misprinted, from the middle onwards, as to make worse nonsense than I did. You will see the New Bedford people are in a rage. I have allowed the colored race superiority of the affections and sentiments—the upper part of man’s nature; but they want the intellect, too. As for their “demon” of colonization, I did not hint at it.

Letter to the Central Committee of the Ohio Convention of Colored Freemen, 21 Dec 1851

You are pleased to ask my views ‘as regards the present position and future prospects of the colored race in this country.’

You submit to me a great problem. Its terms include the colored population alone. But I presume you would not exclude from contemplation the welfare of the white race, so far as that can be promoted by a full regard for the rights of the blacks. Fortunately, however, I believe there is no real conflict of interest between the races. The eternal laws of justice and right would promote the welfare of both. If either resists these laws, it will deserve, and must ultimately receive, an avenging retribution.

In the first place, I think it neither probably nor desirable that the African race should die out and leave that part of the earth to which they are native and indigenous to the Caucasian or any of the other existing races. There are vegetable and animal races which we may lawfully desire to see supplanted by other kinds of vegetable and animal growths; nay, there are tribes of the human family whose existence we may not wish to see continued, provided always that they dwindle and retire in a natural way, and without exercise of violence or injustice to expel them from the earth. But writers on the characteristics of different races of men ascribe to the African many of the most desirable qualities belonging to human nature. As compared with the Caucasian race, they are indeed supposed to be less inventive, to have less power for mathematical analysis, and less adaptation for abstruse investigation generally, are less enterprising, less vigorous, and are less defiant of obstacles. But, on the other hand, there is great unanimity in according to them a more cheerful, joyous and companionable nature, greater fondness and capacity for music, a keener relish for whatever, in their present state of development, may be regarded as beauty, and a more quick, enduring and exalted religious affection. The blacks, as a race, I believe to be less aggressive and predatory than the whites, more forgiving, and generally not capable of the white man’s tenacity and terribleness of revenge. In fine, I suppose the almost universal opinion to be, that in intellect the blacks are inferior to the whites; while in sentiment and affection, the whites are inferior to the blacks.

Under these natural conditions, may not the blacks develop as high a state of civilization as the whites? Or, what is perhaps the better question, may not independent nations of each race be greatly improved by the existing independent nations of the other? I believe so.

I believe there is a band of territory around the earth on each side of the equator, which belongs to the African race. Their Creator adapted their organizations to its climate. The commotions of the earth have jostled many of them out of place; but they will be restored to it when reason and justice shall succeed to the terrible guilt and passions that displaced them.

Do not these considerations bear directly and strongly upon the great question, as your letter expresses it, ‘of future prospects of the colored race in this country’—that is, as I understand you, the colored race, both bond and free? I think they do. While therefore, it is our duty to do whatever we can to ameliorate the condition of the colored people among us, and especially to resist the pro-slavery action of ambitious politicians and of the General Government, it is your duty to project some broad and comprehensive plan, and devote all your energies to its execution, which shall look to the ultimate redemption and elevation, within the shortest practical period, of your brethren in bondage, ‘in this country,’ and throughout the globe. Gird yourselves for this work. Seek for wealth as a means of education, advancement and influence; build yourselves up as far as possible into a condition of independence; let your hearts be penetrated with the moral and religious fervor which belongs to a good and holy cause, and may God bless your endeavors.

Very truly yours,

Horace Mann

Horace Mann, who was invited to address the convention on the present position and future prospects of the colored race in this country.