Once again “Stacks” sings a song of the Antioch College Library, featuring vocals by Patricia Aldred, class of 1952. Her brief history of the early College Library originally ran in the November 1952 Antioch Alumni Bulletin when Horace Mann Library (The Music Dept. for some and Weston Hall to other, later vintages of Antiochians) had exceeded its capacity and was about to be replaced with Olive Kettering Library. Pat married George Mrazek and together they established The Communications Co., Inc. in Chicago.

******************

Mann Library: 1853-60

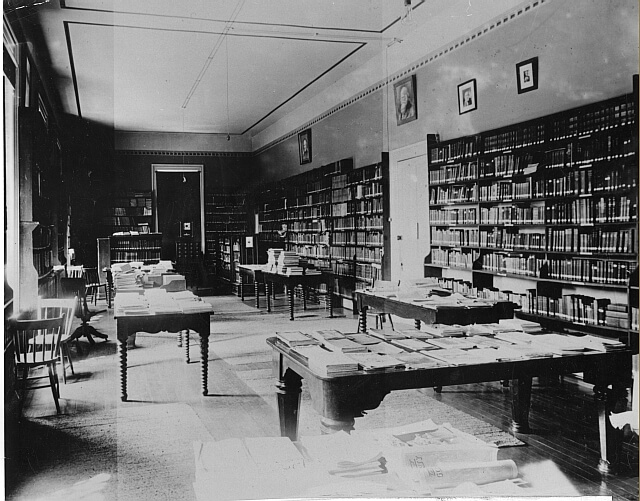

The College Library when it was on the second floor of Main Building, c.1890.

By PAT ALDRED, ’52

Partricia Aldred, class of 1952, as a first year student at Antioch College.

Launching a Library

As might be expected by anyone who has steeped himself in the Antioch of the 1850’s—at least to the extent of taking a good look at the century old Main Building with its tall towers the “Library Apparatus” created by the college founders was by no means commonplace.

To be sure, the library’s unusual qualities were probably due to the intellect of President Horace Mann as well as to the glorious dreams of the Christian Connexion—it was the Christians who had envisioned Ohio towers so lofty that the Gulf of Mexico might be visible from their heights. But it was in the selfsame conviction of future greatness that the Christian founders of the College dared summon Mann, the foremost educator of the country, to be the first president of their poorly endowed and unfinished frontier enterprise. Neither the Christians who were organizing the College and writing about it in their newspaper, the Christian Palladium, nor Horace Mann, who gave up home and friends and civilization to come west, intended, to build just another small church school. The story of the library may help to prove that what they built was indeed something more.

The need for funds to buy library books is first mentioned in the Palladium early in 1851, two years before the College opened. More definite arrangements were made a year later when the provisional trustees of the College appointed a committee of twenty Christians, many of them ministers, to solicit “Books and Funds.” The committee launched its campaign with a burst of eloquence cannily directed to every Palladium reader.

Friends of the College were to give for the sake of their sons, daughters, and friends, who would peruse the books. Publishers were reminded of the increased sales their benevolence would naturally bring them, for would not each of the five hundred to a thousand students anticipated need, on graduating, a library? And would they not choose such books as they had learned the value of in the college library? “Hence…the gift of a single copy to the College library might be the means of subsequently selling a thousand of each to the students, graduates, and friends of the institution.”

The appeal to authors was similar. But to benevolent, philanthropic friends of a free and liberal education, it was pledged simply that the books would be used “as may best promote the interests of humanity and the cause of God.”

Collecting in Person

The committee did more than write high-powered advertising, however: they went collecting in person. The man who excelled at this task was the Elder Isaac Walter, or so his admiring biographer, the Rev. A. L. McKinney, tells us. Walter collected 210 books in Baltimore in one day. Moreover, he made up a special bookplate, headed by “Antioch College” and the name of the donor, with “Elder Walter” in one corner. Volumes with this bookplate are still to be seen in the “old library,” a part of the original Antioch library which is kept in the Antiochiana collection of the present library.

The ministers did not limit themselves to collecting “religious” works: among the volumes which bear Walter’s bookplate are Horace Greeley’s Hints Toward Reforms, presented by the author; a book on the slave colony of Jamaica after sixteen years of freedom; and a variety of other titles. It is true, though, that the library finally assembled did include a good many lives of ministers, books of sermons, tracts, and an impressive work entitled The Genealogies Recorded in the Sacred Scriptures According to Every Family and Tribe with the Line of Our Saviour Jesus Christ Observed from Adam to the Virgin Mary. Of this nature may have been a good many of the 1500 to 2000 volumes reported collected by October, 1852.

Possibly the ministers themselves were dissatisfied with the results of their canvassing or possibly Horace Mann had a premonition he would be. Anyway, a member of the committee wrote Mann that the new president was expected to select other titles later.

Mann’s Efforts

One long sunny room on the second floor of “Antioch Hall” was set aside for the library (Partitioned now, the room is occupied by the English Department). When Mann arrived in September, 1853, however, the room had neither books nor shelves. “In vain for that,” he complained a year later, “had the art of printing been discovered.”

Mann proceeded to write to various authors and poets of his acquaintance, asking that they donate copies of their works. Still in the “old library” are the phrenological works Mann purchased with a gift of $100 from a friend, the phrenologist George Combe.

He then set about selecting books to be purchased. By November, 1853, he had spent $835.01 of the thousand dollars allotted him. With funds available limited he had to select books with care.

Fortunately, a list of suggested titles has been preserved along with bills and other library material, in the Antiochiana collection, which sheds light on some of the considerations involved. Perhaps this is a list of needs submitted for Mann’s .consideration by a colleague, for the titles are often supplemented by capsule critiques. And what stands out in these critiques is the nonsectarian spirit, the liberal faith in man’s reason, in which the College was founded—so strange a faith for a college of that day in the backwoods of Ohio! One historical volume is included in the list because it gives the “Catholic view.” Others are praised as “liberal,” “ample,” or “accurate.” Archibald Alison’s Europe from the French Revolution, a best-seller of the period which was even translated into Arabic, is disparaged as having “too much of the War Spirit,” though a “glowing and elaborate account.” Herodotus is recommended as “a specimen of the manner of ancient historians,” Hume for his graces of style. Just about every historical period is covered.

The compiler does not seem to have been much interested in fiction, except Sir Walter Scott (five titles’ worth) to “give an idea of Scott” and “please.” And Mr. Tennyson’s In Memoriam is plugged as “just published—an exquisit tribute to friendship.”

Judge of Books

Mann himself judged literature chiefly in terms of its moral effectiveness. He liked biography of the great and good, whose tendency was to “reproduce the exellence it records.”

He infuriated Richard Henry Dana by suggesting that he rewrite Two Years Before the Mast so that it might contain “more valuable information which would be useful to young persons.” Mann said that “a narrative, a description, had no value except as it conveyed some moral lesson or some useful fact.” (Dana was still pretty mad when he wrote about the. incident in his diary. “He had but one idea in his head, and that was the idea of a schoolmaster gone crazy, that direct instruction on matters of fact was the only worthy object of all books…In fact, I never saw such an exhibition of gaucheness and want of tact in my life.”)

The books Mann selected for Antioch, however, indicate he was a man who interpreted his own principles pretty broadly. The sheets of paper on which he listed the titles he wanted are now a part of the Antiochiana collection.

The range of titles includes Pascal’s Thoughts on Religion; biographies of Luther and Mohammed; Use and Abuse or Right and Wrong in Relation to Labor of Capital, Machinery and Land; books on China, Norway, India, the culture of the North American Indians, and Russian sovereigns; the works of Lady Mary Montagu and Mme. de Stael; the Privy Purse Expenditures of Henry VIII find Edward IV; Bibliomania, or Bookmadness; a history of Negro slavery; Diet With Its Influence on Man; a volume on aeronautics; and many others. A translation of Confucius·from the German was also requested, but was not available. The list also included Two Years Before the Mast, by Richard Henry Dana.

From other bills, we find Mann spent $150 for lawbooks, and sent $100 to an agent in Europe for unnamed books. He also spent $9.00 for magazines, likewise unnamed.

In contrast to these expenditures, a history of Ohio colleges tells us that Denison, for instance, twenty-one years old in 1853, valued its whole library in that year at only $400.

Old Uses

Still, the contents of a library are not everything. Its use is perhaps even more important. And it is in the way its books were used that the true uniqueness of the first Antioch library lay. It was related, of course, to the academic program.

The usual college course before 1850 was “classical”; it consisted mainly of Greek, Latin, and higher mathematics. It did not require much use of a library. In the early fifties Yale and Harvard, and a few others, offered a B.S. degree, but in most institutions the classical emphasis remained heavy and electives were rare. The latter did not appear at Oberlin until 1875.

Antioch offered in its first catalog not only the customary classical .studies but also political economy, a variety of sciences, didactics, and physiology and hygiene; it also allowed several electives.

The 1859-60 Antioch catalog carries this note: :All the students connected with this institution have free access to a Library of about 4000 volumes, which has been carefully selected with especial reference to their wants.”

This liberal attitude toward the way a library should be used is not generally reflected in the colleges of the time.

At Columbia only such members of the freshman class as were specially designated by the president were permitted access to the books; at Antioch, even the preparatory (high school) students were given free use of the library.

New Uses

As early as the [eighteen] sixties, Antioch kept its library open three hours a day, from two to five, every afternoon except Wednesday and Sunday, and permitted students to thumb through its books in person. Usually the literature professor was in charge, or a student, and he or the borrower wrote down the date and the title of the book, or its “shelf number,” in a big ledger marked off with each student’s name. (The Dewey Decimal System and card catalogs were yet to come.)

Why was Antioch so liberal? Perhaps freedom was easier at a small college than at a large university, as may be the case today. Mann’s whole educational philosophy was based upon an identity of interest between instructors and instructed, with sympathy and mutual affection between them. And according to an account by the Rev. Henry Clay Badger, one of Mann’s former pupils, Mann’s own teaching methods encouraged independent investigation of assigned topics (and, presumably, use of the library), “not so holding his flock to the dusty, travelworn path as to forbid their free access to every inviting meadow or spring by the way.”

Built on the site of his home, the present Antioch Library bears Horace Mann’s name. It is overcrowded, with little more study space than was available in the room in “Antioch Hall.” Mann might disapprove. But if his ghost is hovering about the building, browsing and savoring new volumes, it surely enjoys watching today’s Antiochians as they personally search the stacks and depart with books they have honorably charged themselves.

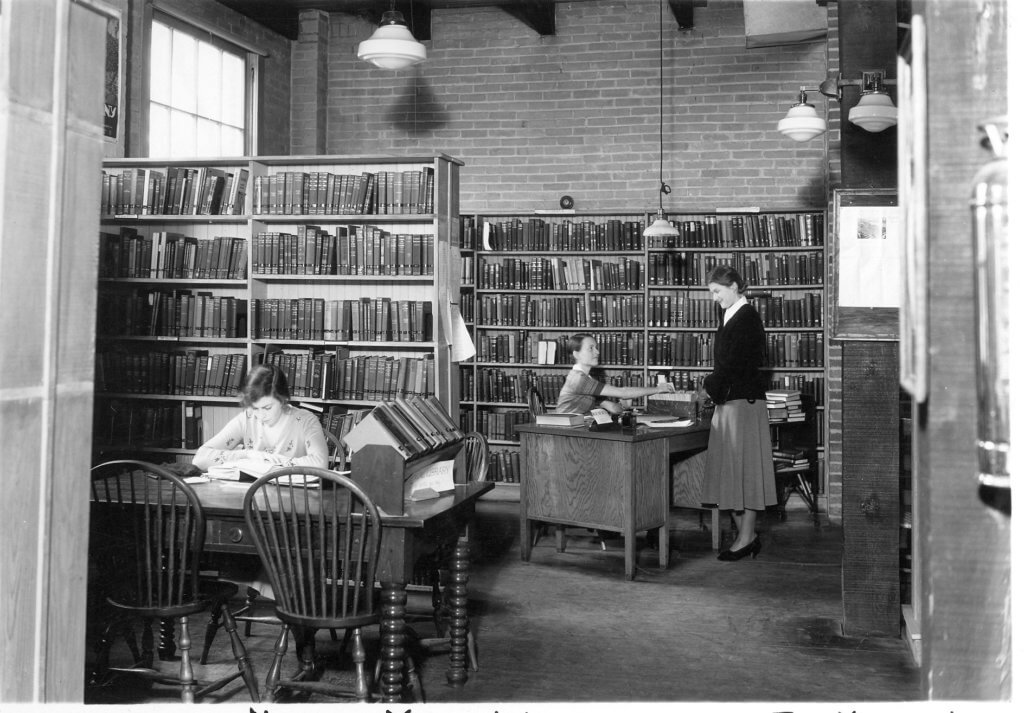

Inside Weston Hall when it was Horace Mann Library, c1940.

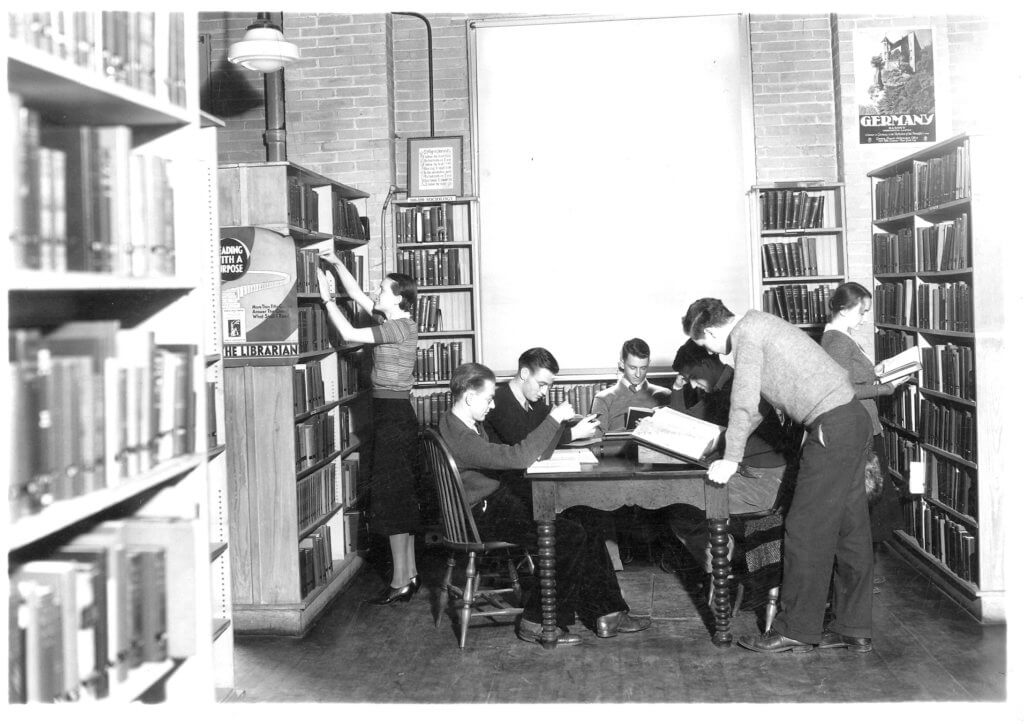

Inside Weston Hall when it was Horace Mann Library, c1940.