One of the most interesting figures ever to serve on the Antioch College Board of Trustees, Charles F. Kettering knew a thing or two about research. He held over 140 patents, most of them while head of research for the General Motors Corporation. In the Fall of 1943, with nearly all the world engulfed in savage war, he spoke of research at a modest but propitious event that took place at Antioch College: a ceremony to formally retire a very important loan. According to The Record of Oct 18th of that year:

The original loan of $325,000 was procured in 1920 in order to finance the Co-Op plan, the recruitment of a new faculty, and the modernization of the dormitories. The debt was partially paid off in small sums up to a year ago, the total reduction then amounting to $71,000. Last year, a drive initiated by President Henderson to raise the remaining $253,000 pleasantly surprised all concerned by being successful. It is the paying off of this last amount that is the occasion of our simple “family party.”

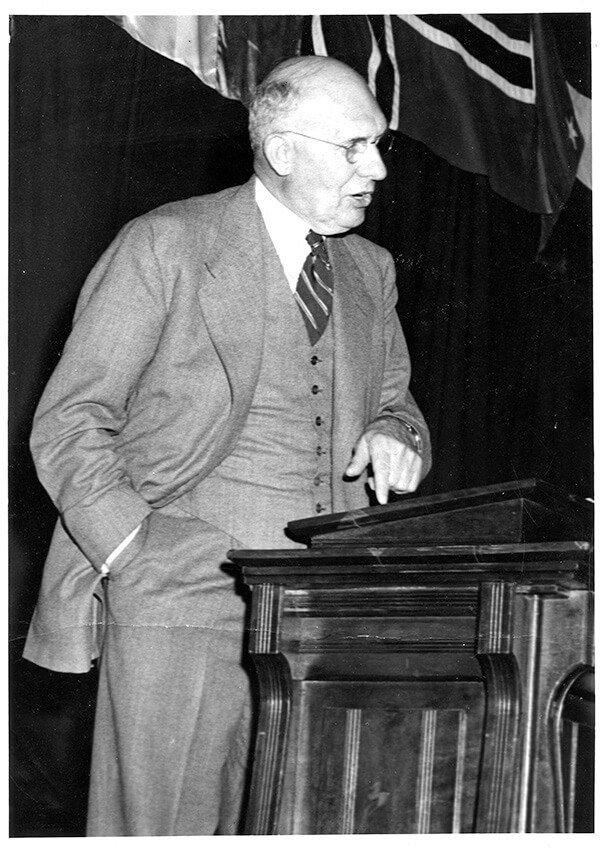

That day’s festivities followed the fall Trustees meetings: a review of the unit of student soldiers on campus (a story for another time), then a note-burning ceremony and then addresses in Kelly Hall by Kettering, former president Arthur Morgan, and Algo Henderson. All three discussed the future in some way. Kettering’s remarks, reprinted here, are exemplary of his inimitably practical nature, his rather surprising patience, and his plain spoken style.

********

Address by Charles F. Kettering on the occasion of paying off the $253,000 balance of the reorganization debt incurred by Antioch College in 1920. October 23, 1943.

Antioch, Research, and History

Charles F. Kettering, President General Motors Research Corporation; Trustee, Antioch College, Beginning 1920

Having been in research all my life, I am not very interested in the past, passably interested in the present, and almost entirely interested in the future. Now that doesn’t mean I am not interested in this celebration today. You see, Antioch was in the future when we started.

There is a saying hung up somewhere around the General Motors laboratories that a lot more people would have crossed the ocean if they could have got off the boat in the middle of a storm. I think that was not the spirit among those interested in Antioch. Antioch ran into plenty of storms, but we had a very definite objective and the venture has been well worth staying through. Running into trouble is not important. There is only one sure thing about any new idea—I guarantee there will be trouble. I guarantee trouble to anyone who strays from the beaten path. If there is any one single weakness in our educational system, it is that we do not advise people they are going to run into trouble, and then they run into it unexpectedly.

Especially in research, we underrate the length of time that it takes to do anything. For instance, when we started the photosynthesis research on campus here we knew it would take a long time—maybe twenty years. Now I hope that all of you who are engaged in that particular research are married and have a good many boys and girls because I think it is going to take about three generations to do the job! You can’t start these long-range studies and expect them to happen within a prescribed time.

One of the great difficulties about research and development is that somebody is always trying to budget it and forecast it. It can’t be done. It is not important, for instance, whether Antioch has reached its goal, but it is important if Antioch is after the right objectives—the things worth while doing.

I speak of research: that is all Antioch has been to my mind. Now I am not idealistic about research—it is a long slow process. Idealism doesn’t work because it is impatient, and research is a tedious process. But I think I can always determine whether a particular piece of research is worth doing.

Sometimes a research project starts with a flash, you know—and then comes down again like a sky-rocket. Antioch wasn’t that kind of thing. Some say, “It isn’t an invention unless there is a flash of genius”—to which I say, then there are very few inventions! The flash is usually what doesn’t work, and the genius is sticking to it until it does work—and that is time consuming. Now Antioch started out with certain definite objectives, some of which may have been good and some not good, but which were constantly revalued and sifted out as they unfolded. I don’t think discarding objectives is important, as long as you are starting out with a good idea. In a research experiment, it’s not so much where you are at any given time as why you are there that is important. If you start out along a certain line, you might, after a period of time, even wind up where you started, but that’s all right if along the way you’ve selected the good things in your program and discarded the bad things, and have a logical reason for being where you are.

In education generally, there is one thing we find. The reason we have wars and the reason we are going to have some more of them is that we don’t teach in the colleges and universities and other educational institutions one of the fundamentals, the study of the future. I have no objection to studying history—history is very important. But I think we have been studying history the wrong way. We have been looking at the past and backing into the future. I want us to back into history far enough to get a good look ahead. I have been trying to get a word for the opposite of history. The word ‘hysterics’ has been suggested. I think we can logically study the future provided we can recognize the factors we have to deal with. We can find these factors by studying the past, yes—but in the light of the present and the future.

In the study of the future, what kind of people are we going to have to deal with? Some idealists think they are going to be a different kind of people. But they are going to be the same kind of people we have now. That is why it is not postwar planning but postwar wishing, if we presuppose that human nature is going to be different after the war from what it was before. In all of our plans for the future we must take people into consideration as they are. Also we have to make long-range plans and that is hard to do in a politically organized institution. The length of time it takes outlives a political administration. But at present, even our long-range plans are made to terminate within a specific term of office. It is very difficult to get a long-range plan of anything through governmental institutions. Long-range planning has to be handled through independent, long-range organizations and institutions. That is one place the colleges can contribute.

But if we are going to have the kind of world we want to live in—the picture-book kind that we would all like to have—we must recognize that there is some groundwork to be laid now. I have, as you know, been interested in co-operative education. I was one of the first people interested in co-operative education at the University of Cincinnati, and I have been associated with Antioch since its reorganization. Right now there is the new Northwestern venture in which we are going to do a very different type of thing. But whatever the method, I don’t consider co-operative education just a system where students go to school half time and work half time. The aim is to tie the students in with people and the way they live. Essentially, it is the principle of integrating the academic and the practical world, of studying the past in the light of the present.

I am glad to be here today and see this phase of the work finished. But twenty years is a very short time in the development of the ‘Antioch idea’. It is only a beginning. I can only say that I am most hopeful of the immediate future. For the long-range future, the greatest factor of security is that the base of interest in the College has been broadened. I know the program will go ahead.