“It was a true teamwork situation, especially when things were really tense,” Susan said. “We yin and we yanged.”

That was the life they led: thrilling, spontaneous, meaningful, and always side-by-side.

Susan lost her yang in January, when Clifford died of Covid-19 in Washington. He was 73.

There, he and Susan — they had met in college years earlier — learned that their love affair could be transformed into a professional partnership.

A manager at CBS hired Susan with one stipulation: They could not carry their personal life into work.

In the 15 years they worked together at CBS News, co-workers were often surprised to learn that they were married.

“Mom and dad were like the go-team,” said Peter Feldman, their now-38-year-old son, whose earliest memories were from overseas when his parents left him with the hotel bartender as a babysitter. “I was raised in a household that is extremely worldly.”

And through it all, Susan described her husband as ferociously curious, humble, collaborative and famously moral.

“He always tried to find that visual that added depth to someone’s pain or someone’s excitement,” she said. “That’s what made him an extraordinary photographer.”

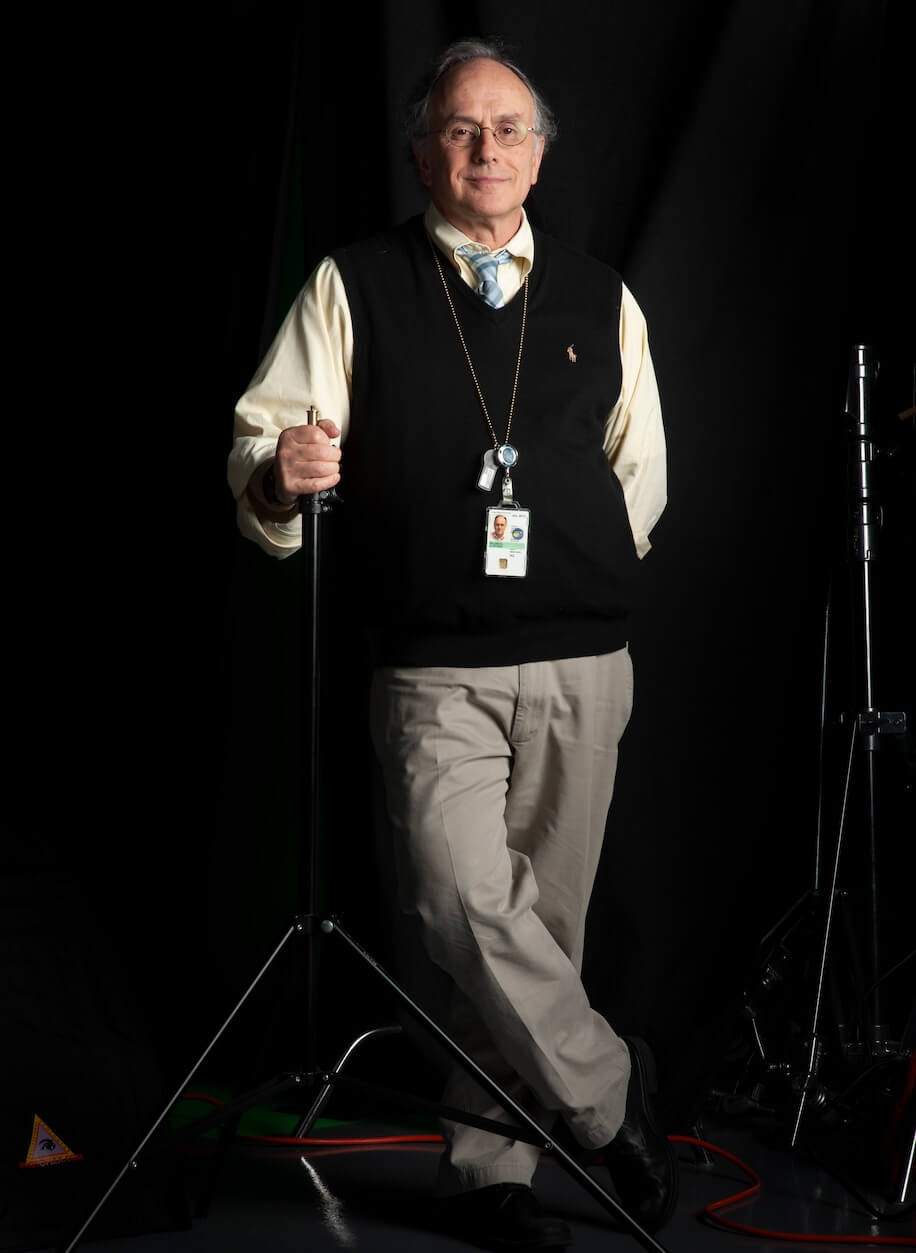

Clifford later worked as an assignment editor and field producer for NBC News, where he covered the White House, Capitol Hill, the Pentagon and State Department before he left to help structure the initial newsgathering operations for Fox News in D.C.

Clifford’s coverage of the space shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003 caught the eye of NASA-TV, which asked him to come in-house and reinvigorate how the space station shares its footage. In 2017, he led a project that displayed live location tracking of the eclipse across the country.

Together, the Feldmans and their two children traveled the world. They watched Princess Diana wed, and Youngstown and Pittsburgh crumble with the steel industry. They chronicled coal mine accidents and spent 15 days on Air Force One following Nancy Reagan.

Between trips, he found time to coach his daughter Kathleen’s youth soccer team and scour the paper for weekend activities with his son. He became a lover of mystery books, crossword puzzles and D.C. baseball.

Clifford received one of NASA’s top civilian honors, the Exceptional Public Service Medal, for his work on the Total Solar Eclipse broadcast.

He spent his final six months working on how to cover the landing of the Perseverance Rover on Mars. At 73, he had no plans to retire.

“We have lots of friends who’ve had impressive careers as neurosurgeons and litigators, and later in life, they’d tell you how bored they were,” Susan said. “He was the person who said, when I get that way, I’m leaving. But he got up every morning wanting to go to work.”

Michelle May, communications manager for MORI Associates at NASA headquarters, worked with Clifford for the last year-and-a-half of his life.

“From the younger people to the seasoned people, they came to Cliff for advice and to tell him what was going on professionally for them,” she said. “Cliff could have been around for years.”

Perseverance landed on Feb. 18, just over two months after the Feldmans caught the coronavirus.

Susan went to the hospital on Dec. 8. Clifford went two days later and never came back.

His final words were to Susan.

“He told me that I was the love of his life and then he started to cry,” Susan said. “And I told him he would be just fine.”

She delivered remarks at the memorial service of her beloved husband, whom she described as a “quiet, understated and beautiful man.”

“I was so lucky to have had him for so long, but it wasn’t long enough,” she said. “I so deeply loved him.”

Clifford’s black JanSport backpack that he took to the hospital is still sitting in the same dusty corner where their daughter put it the day he died.