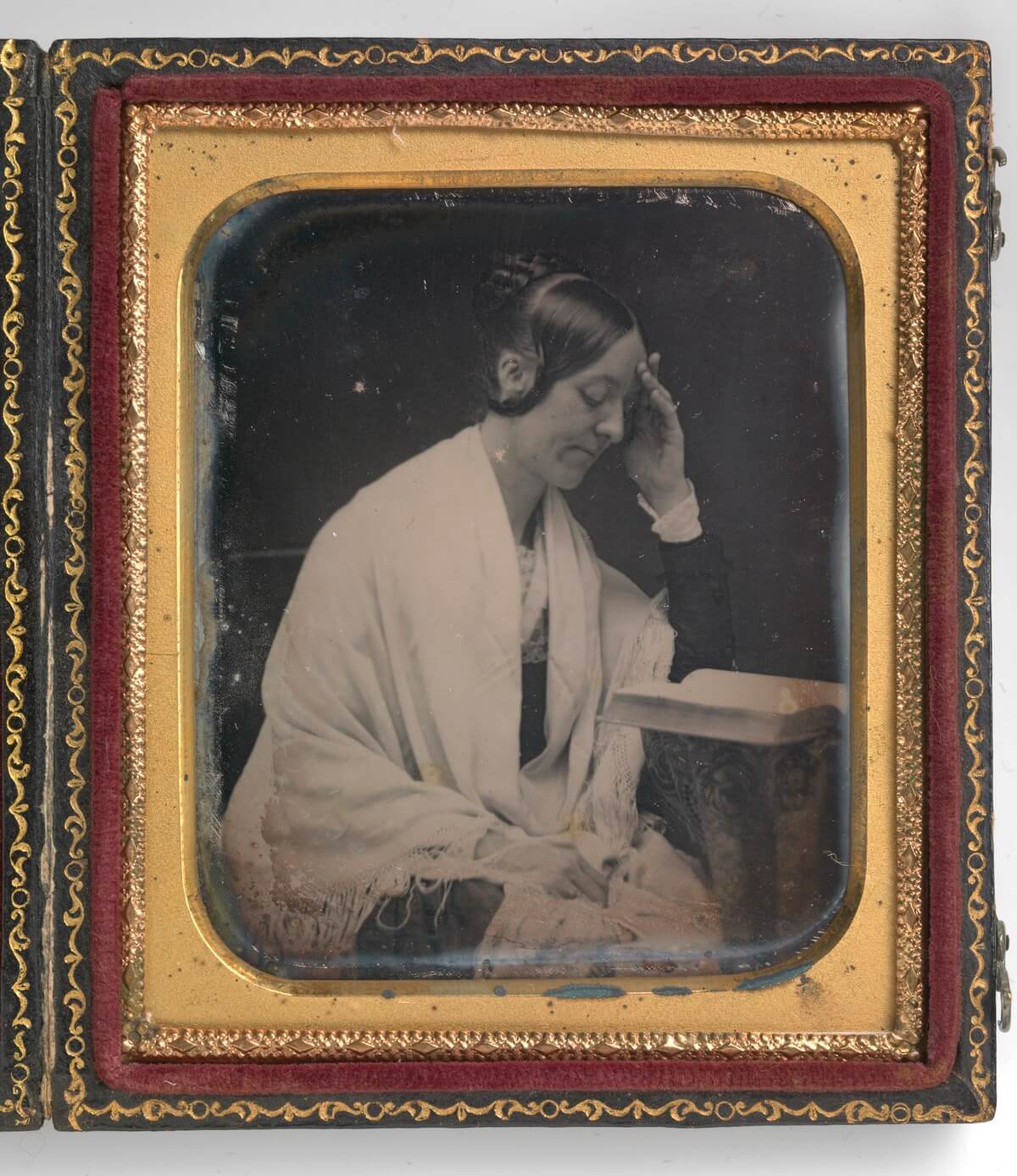

Margaret Fuller (also illustrated in header image)

Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) was a formidable intellectual presence whose life, although brief, defies encapsulation. Once considered the most widely read person in New England, she was the first editor of the Transcendentalist periodical The Dial established by Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1839 and later the first full-time book reviewer in American journalism for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune as well as its first foreign correspondent. Her most famous book, Woman of the Nineteenth Century, published in 1845, is considered a seminal work in American feminist thinking, which 10 years later prompted the novelist George Eliot to write a comparative essay about Fuller and Mary Wollstonecraft.

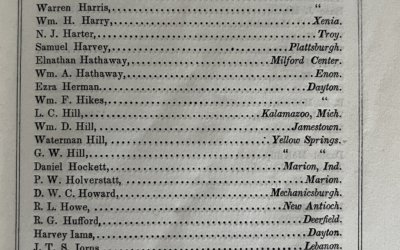

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody

Beginning in 1839, both as a way to edify women with little access to higher education and as a source of revenue, she began to hold her now famous “conversations.” Though she probably borrowed the term from her friend Bronson Alcott’s Conversations with Children on the Gospels, as Megan Marshall wrote in her monumental 2006 triple biography The Peabody Sisters: “Such was the force of Fuller’s personality that, as with anything else she appropriated from others, the term ‘Conversations’ would afterward always be associated with her.” Fuller hoped to facilitate discussions between equals in which she would serve primarily as a “nucleus of conversation,” but she was just too accomplished and forceful a personality to do anything other than lead. As Elizabeth Peabody, who recorded the proceedings for posterity, wrote many years later: “I think no one attended that course who did not pronounce [Fuller’s] initial statements and occasional bursts of eloquence the most splendid exhibitions of conversational talent, not only that they ever heard, but that they ever heard of.”

Here reprinted from Antiochiana’s collection of Peabody Sisters Letters are some of those proceedings taken down by Elizabeth, though recopied by her sister Mary. By the time of this session, Fuller had moved on to Greek mythology, a subject with which members had at least some familiarity. She had hoped to answer the more difficult questions facing the women of her time, as she had written in a letter to a friend the previous summer: “What were we born to do? How shall we do it? Which so few ever propose to themselves ‘til their best years are gone by.”

Undated (Fall 1840?) (Comments on Margaret Fuller’s Conversations, in hand of Miss Mary Peabody)

At first we took up the subject of Grecian mythology of which I told you. The second conversation was upon Apollo. Having stated him as the embodiment of the element of genius we proceeded to the various fables in which he figures, & traced through them the Greek idea of respecting the element of the human mind, its characteristics, its actions, its destiny, & the conversation ended with the questions how far the possession of genius was compatible with—or assistant to happiness & virtue— & though these great questions were not settled it was useful to discuss them. Venus was taken up next—not as the Goddess of Love but as the Goddess of Beauty—her birth in the eye of the Greek from the graceful foam of the ocean, &c—but this subject was not pushed through the fables. It went into the abstract question of what is beauty—on which almost all wrote essays attempting to define it. Two or three gave some admirable definitions of it (as far as the immortal essence, spiritual beauty, may be defined) & the rest wrote little poems (in prose) upon where beauty was to be found.

The next conversation was upon the fable of Cupid & Psyche—but I cannot do justice to that in a letter. In the first place, Miss Fuller told the story with a grace & beauty that was of itself an exquisite delight to hear. It was immediately taken up as the Greek attempt to set forth the universal fact of the trial of the soul on the earth, its purification by means of the sufferings its own mistakes bring upon it, & its final redemption and immortality. The question of how much analysis should enter into our dealings with our own and others’ souls—how much was inevitable, how much was desirable, what was excessive—also occupied us.

The 6th conversation was on wisdom under the head of Minerva, and the mechanical part of art under the head of Vulcan.

The 7th conversation we had a criticism on our essays on beauty, & Miss Fuller read an answer to them she had written herself. It embodies and admirably arranges all the best ideas of our essays.

In the 8th conversation Miss F. proposed to leave the subject of Grecian mythology—for tho’ we had only touched the superficies of this great subject (which embodies the highest intellectual action of the most cultivated nation on earth, & is therefore commensurate with the thoughts of Genius) yet we had gone enough into it to indicate in what point of view it was to be studied—so as to avoid that unhappy vulgarity of association to which I suppose the ignorance and consequently the grovelling imagination of the uncultivated have condemned not only themselves, but many of whom better things were to be expected. She proposed that we should ask ourselves what is the radical difference between poetry & prose—, as an introductory step to seeking out some sound principles of criticism. That day was taken up in defining that in nature which it was the object of poetry and the fine arts to manifest—that which Coleridge calls “Poesie”; & in discriminating it from prose.

The next conversation was upon the difference between the fine arts, including Poetry, as one, ending with a definition of poetry. The next conversation was upon the classifications of poetry into Lyric—Epic—dramatic &c, & a question as to the comparative advantage of these forms for expressing poesie, & what admixture of prose was necessary in order to bring them to human capacity—also whether satire was poesie—how much of a satire was that element & how much prose.

The next conversation was upon Burns & Midsummer Night’s Dream—but endeavouring to remark upon these we came across two other questions of suffering to the intellectual as well as the moral character, & the other the definition of the two words imagination & fancy. We found ourselves so vague in the use of these words, that Miss F. proposed we should write upon them, and bring our essays the next time. Accordingly last Wednesday we carried about a dozen which she read aloud and commented upon, we all of us also making our comments.

(Probably copied from a letter written by Miss Elizabeth P. Peabody.)

“Songs From the Stacks” is a regular selection from Antiochiana: the Antioch College archives by College Archivist Scott Sanders.