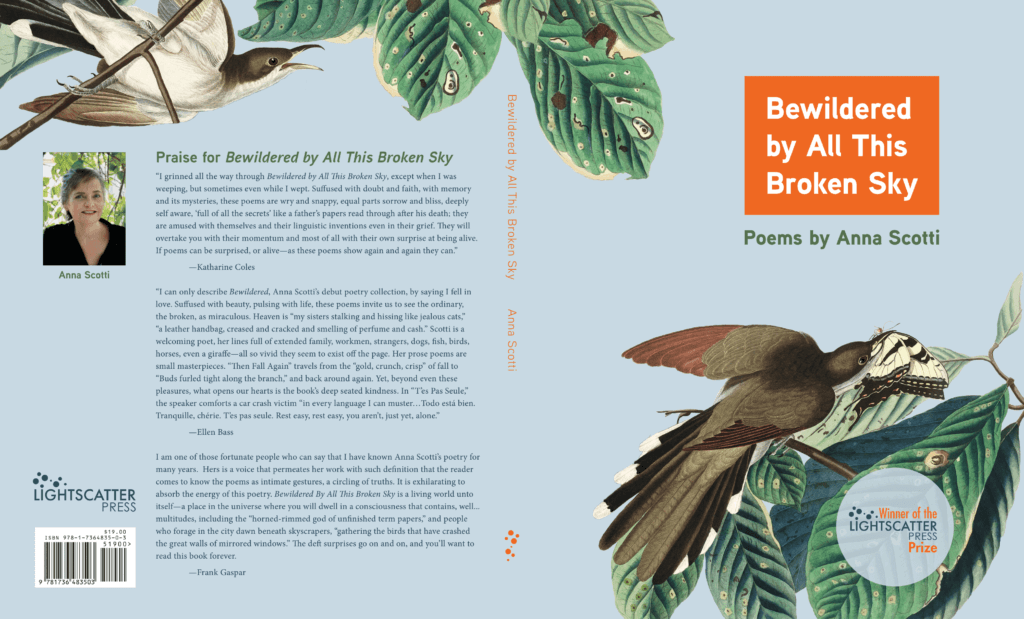

Anna (Coates) Scotti ’80 is a widely published writer and poet, born in Washington, DC, who was awarded the first-ever Lightscatter Press Prize for her collection of poetry, Bewildered by All This Broken Sky, which is set for release in April 2021.

Anna (Coates) Scotti ’80

Anna enrolled at Antioch College at a young age and was given free rein to explore different interests and majors, graduating with a focus in Psychology. Anna earned her MFA at Antioch University Los Angeles in 2007 and has worked as a journalist for the Seven Sisters women’s magazines, as well as for InStyle, Buzz Magazine, and others. Anna currently lives in Southern California where she works as a Middle School teacher. Her poetry has appeared in The New Yorker since 2016 and in a variety of literary magazines. Her short stories can be found in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine.

Anna’s young adult novel, Big and Bad, was published in 2020 and she is delighted to share her new book release, Bewildered by All This Broken Sky, a book of poems that “help us to see the miraculous in the broken, the every day, the ordinary, and are suffused with radiant language and deep kindness,” writes poet Ellen Bass.

Read our interview with Anna below to learn more about her experiences at Antioch College, her path to Creative Writing, and her advice to current students interested in publishing.

What made you decide to apply to Antioch College?

I was a very young freshman—just 15 when I started—and although I was accepted at several schools, only Antioch would let me start right away without taking a gap year. So that decided it! The gap year was a new idea then, and was sort of frowned upon in general.

Why study Psychology?

I changed majors so many times, but ultimately psychology classes were the most interesting to me. I first declared a major in “journalism,” which in retrospect is very funny because I didn’t know what that meant. I thought it meant “novelist,” but as it turned out, I did eventually work as a journalist for about five years, writing for women’s magazines such as Redbook and Ladies Home Journal, as well as for InStyle, Buzz Magazine, and others.

When my cohort entered college, there was an idea that college was a place to find yourself, to discover your interests, and develop your talents without necessarily focusing on a plan to earn a living upon graduation. In the current climate, it’s very different—students get a lot of pressure to prepare for a college major while they are still in high school.

Was there a teacher or perhaps a class at Antioch that helped draw your focus to writing and poetry?

I took a student-led class, which was a new idea, at least to me. One of the two teachers was Sarah Gorham, and the other was Debbie Gimelson. I remember being mind-blown when they started to (civilly, eruditely) argue with each other about a line in one of my poems. I still remember the line! “They raise their eyes like the saints we have painted,” Sarah said the ambiguity couldn’t stand—was it the eyes that were raised, or the saint?—Debbie insisted that it could. I don’t remember the rest of the poem, or whether the ambiguity was intentional, but what I do remember is the feeling of having my work really closely examined by two poets who seemed impossibly sophisticated and erudite from my humble perspective. When I started writing poetry again, decades later, I learned that Sarah Gorham co-founded the well-respected Sarabande Press! That was a fun Antioch connection.

What were your Co-ops? Did you do a study abroad?

I never did a study abroad, but I had great Co-ops, mostly science-based. One of the best was at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. I worked in the herpetology lab in the mornings, cleaning snake specimens that had been harvested from the South China Sea some fifty or sixty years before, and in the afternoons I was in primatology. I also spent a winter on a ranch in Nevada where chimps were being taught sign language and a summer in Washington at the Cybernetics Research Institute. A final Co-op at the National Institutes of Health turned into a job where I stayed for a year and a half.

Does an understanding of psychology—or more narrowly, of metaphor and semiotics—hinder the creative process?

Certainly, all knowledge contributes to one’s ability to express oneself articulately, but it’s equally true that we become more inhibited as we grow older and more knowledgeable. It’s the rare Jackson Pollack who throws paint at a canvas in adulthood, or Emily Dickinson, or t.s. eliot, who rewrites the rules of punctuation and capitalization in verse.

But that’s probably a good thing. Unfettered creativity is a bore. It’s delightful to watch a toddler dip her hands in fingerpaints, then onto paper, or to hear a fourth-grader struggle to create a simple rhyming poem about pumpkins and witches on Halloween. But these early creative endeavors would not be as charming in an older child or an adult. They are delightful because they are clear signposts along the way to something greater. They are promises that the creative spirit lives in the smallest child, and that everyone has potential yet to be realized.

It’s fair to say that an understanding of metaphor helps us tap into a deeper recognition of what it means to be human. For example, it’s one thing to understand that water symbolizes life—after all, it’s clear and clean and animated as it tumbles over rocks or crashes to the shore. It seems alive, and it’s necessary to life, so the connection is obvious. It’s another developmental step to then recognize that snow symbolizes death—as a teacher, I exult in seeing a new crop of seventh graders realize this each year, analyzing Frost’s Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening. But it’s a different thing altogether to understand that water is a universal symbol of life, in every culture we know of. That comprehension allows us to find an understanding not of one poet’s experience, but of the universal human condition, in William Carlos Williams’s “…barrow glazed with rainwater” or Auden’s “Stare, stare in the basin/And wonder what you’ve missed.”

When I was working on my MFA I took a very interesting class from the poet Richard Garcia. He had us experiment using nonsense words, onomatopoeia—English, and foreign-language words we didn’t know the meaning of—and I came up with a poem I love a lot. It’s called “Babba Ya,” which was one of my daughter’s first “words.” (“Babba Ya: / That first word that meant everything: milk, sweet, warm, sing, and / I need you, need you / desperately.”*) Writing teachers have all kinds of tricks and gimmicks they—we—use to get students going. Some are silly, some are productive, and some are both. It’s about finding that balance between free-flowing, unfiltered creativity, and buttoned-up, fully decipherable meaning. Without the former, there’s no beauty and no fun. Without the latter, there’s no accessibility for the reader, and sans that, what’s the point?

What advice would you give to current Antiochians hoping to follow your path?

It’s the same advice everyone gives the young: follow your dreams. We get discouraged so easily, thinking we’re too old, or that we missed our chance. When you are twenty-five, you’ll look to 30 with a certain dread, and when you’re sixty you’ll look at 40 with longing and nostalgia. The truth is, there are only a few careers that have to be begun early—ballet dancer, maybe. Mathematician. Everything else, jump in when you’re ready, and then swim like mad.

* “Babba Ya” was first published in Chautauqua, and is included in the upcoming collection Bewildered by All This Broken Sky.

Bewildered by All This Broken Sky is Anna (Coates) Scotti’s first book of poems—which can be found here— and is the winner of the Lightscatter Press Prize for 2020 (judged by Katharine Coles, author of Wayward, Flight, and Look Both Ways).

Anna would love to hear from old friends! Please visit www.annakscotti.com to get in touch.