About the Antioch Review

The original mission statement—“We believe in the promise of American life and we would seek the seeds of that promise. This is our purpose in founding a magazine”—has remained essentially intact throughout The Review’s 75-year history. The content of The Review has evolved over the years, with the balance between social and literary matters changing, yet the Review has remained committed to commenting on the temper of the times in story, poem, and essay.

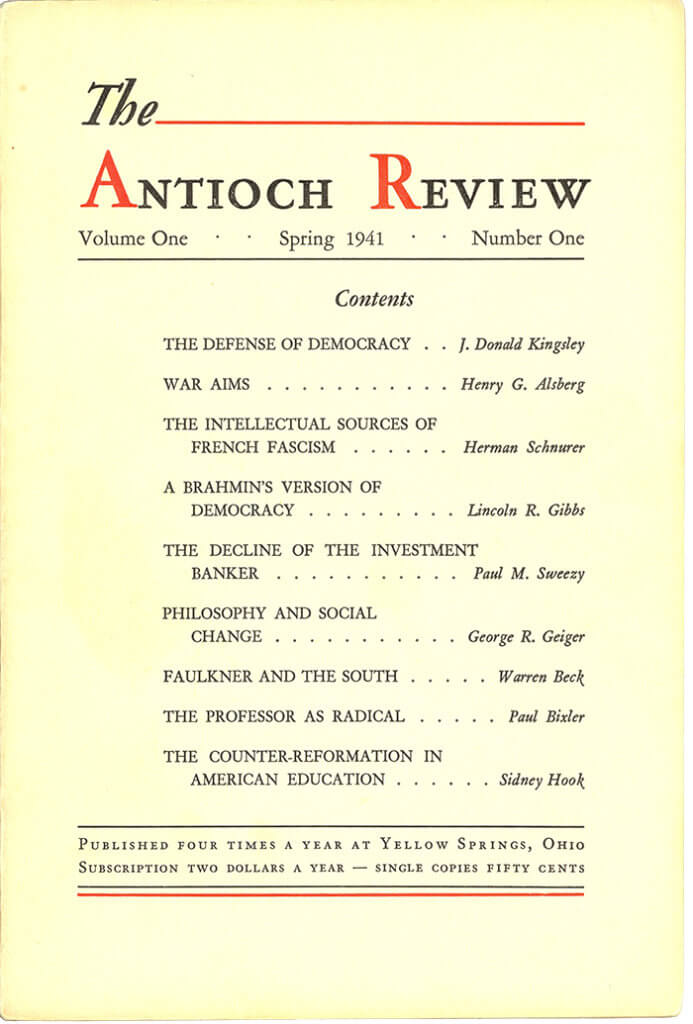

Publishing the Best Words in the Best Order Since 1941

In 1940, a small group of Antioch College faculty met to discuss the founding of a review.

Faced with a world wherein fascism and communism were on the march, they sought to establish a political forum from which the voice of liberalism could be heard.

In 1941 they launched the first number of the Antioch Review and in their statement of purpose gave voice to their political and social concerns.

Their first editorial stated:

It takes, perhaps, uncommon brashness to plunge into the intellectual struggle at a time which Max Lerner has so aptly described as that of “the breaking of nations.” When values are everywhere toppling in the high winds of conflicting dogmas, there are those who would seek refuge in a quiet cloister or an ivory tower. Such an escape is not unattractive; it is impossible. No intellectual, almost by definition, can be indifferent today to the social struggle or to the blackout of learning, literature, and the arts which accompanies defeat in that struggle. If the march of fascism has demonstrated nothing else it is that the scholar is not above society, but is inextricably intertwined in its meshes. The destruction of democracy commences with the erosion of the intellectual classes.

Fist Issue Of The Antioch Review, 1941

The battle for a humanistic social order is, therefore, a matter of prime importance to all intellectuals. Their very existence depends upon victory in that struggle. Yet the argument cannot be allowed to rest on this level of naked self-interest. There are other stakes as well: basic values more precious even than life itself. There is the profound belief in the common man, without which humanism is inconceivable. There is the conception, now heretical over most of the world, that men should be viewed as ends and not as means. There is the revolutionary idea that the social order exists for the furtherance of human welfare, rather than for the glorification of a narrow class. There are a few of the stakes in the gigantic power struggle that is the world’s disease. Civilization today is being challenged in a civil war of unexampled magnitude; a civil war of which the present European conflict is merely one expression. What is at stake is the whole complex of values so painfully wrought in the years since the Enlightenment.

For the intellectual to maintain a lofty “objectivity” at such a time is not merely to commit suicide. If no more were involved than the self-destruction of a handful of ineffectuals, others would have little basis for complaints. But the consequences are more serious than this. We are confronted with a situation in which to be silent is to play the midwife at the birth of another Dark Age. The alternatives are clear-cut and unavoidable. He who does not now speak out assists in the degradation of the democratic doctrine as surely as the outright exponent of totalitarianism.

We do not propose to remain silent and it is our purpose to provide a forum for others who feel as we do. We believe in democracy so strongly that we think it should be enormously extended. We believe that no scholar can fail to view with concerns threats against basic human values, whether they originate inside or outside the country. We believe in an instrumental theory of knowledge and in the application of scholarship to the solution of social problems. We believe that the social role of the intellectual in our time is to employ ideas to further democracy in the fullest sense. We believe in the promise of American life and we would seek for the seeds of that promise. This is our purpose in founding a magazine.

Nineteen forty-one was both a dividing point for the dominant issues and trends of the twentieth century and the beginning of a literary, intellectual, or little (you take your pick) magazine that they hardly could have expected to last out the war. But it did.

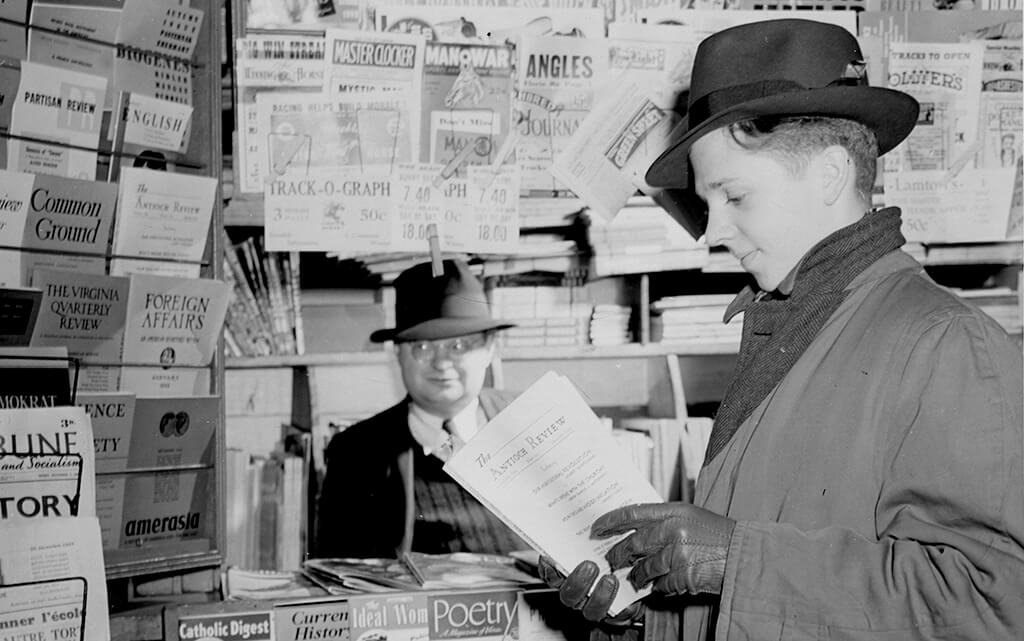

1941 Antioch Review Newsstand Customer

A History of The Antioch Review:

The Survival of the Imagination

By Robert S. Fogarty, Editor Emeritus

The Antioch Review, founded in 1941, is one of the oldest, continuously publishing literary magazines in America. We publish fiction, essays, and poetry from both emerging as well as established authors. Authors published in our pages are consistently included in Best American anthologies and Pushcart prizes. We continue to serve our readers and our authors and to encourage others to publish the “best words in the best order.”

When in 1940 a small group of Antioch College faculty met to discuss the founding of a review, they were faced with a world where fascism and communism were on the march and they sought to establish a political forum from which the voice of liberalism could be heard. In 1941 they launched the first number of the Antioch Review and in their statement of purpose gave voice to their political and social concerns. Nineteen forty-one was both a dividing point for the dominant issues and trends of the twentieth century and the beginning of a literary, intellectual, or little (you take your pick) magazine that they hardly could have expected to last out the war.

But it has been nearly seventy years now and the fact of its survival is no mean feat. Surviving several international wars, the shifting currents of both the ideological and literary marketplace, not to mention the fortunes of its founding patron, Antioch College, it has achieved a certain standing in the world. Librarians from Delhi to Dresden know us, writers and critics read us, and two generations of readers remember the Review for a particular article, story, or poem that caught their imagination. It has never been just one thing, and since the late nineteen sixties it has addressed several audiences, having by that period moved well beyond the social and political agenda of its founding editors.

Despite certain historical disjunctures, the magazine has devoted its space and energies to particular issues and forms. Throughout the history of the magazine questions about race, ethnicity, sex, education, and the American experience have had a large place. Academic questions in their formal sense have not loomed large, and the magazine’s policy of refusing to run footnotes is, in fact, a statement about the non- (rather than anti-) academic nature of the journal. Academics by the score have contributed, but always within a belles-lettres or journalistic tradition. So the magazine was open to both Malcolm Bradbury and Eric Bentley, sans footnotes. The Antioch Review has always avoided narrow academic debates and tried to suggest that although professors may be for the academy, their commentaries can bear on larger social and intellectual processes. And the Review has always tried to be a forum for new writers and ideas in poetry and the short story.

The Antioch Review 1944. Board Sitting from left to right: George R. Geiger (Professor of Philosophy), Lewis Corey (Professor of Political Economy), Paul Bixler (Head Librarian), Freeman Champney (Director of the Antioch Press), J. Donald Kinglsey (Professor of Government), W. Boyd Alexander (Dean of Faculty/Executive Vice Present of Antioch College), Max Astrachan (Professor of Mathematics). Standing in the back from left to right: Herman Schnurer (Professor of French) and Valdemar Carlson (Professor of Economics)

1941–1960

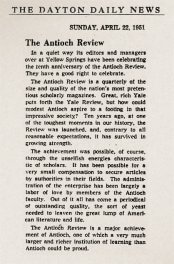

10th Anniversary: Dayton Daily News, April 22, 1951

In the nineteen forties the Review set out a liberal agenda and not surprisingly one finds essays by Carey McWilliams, Victor Reuther, Lewis Corey, and John Dewey appearing within the first five years. In addition, critical articles about “The Women Problem” and “Married Women Workers in the War” appeared in those early years, along with the justly famous “Richard Wright’s Blues” by Ralph Ellison in 1945. Short fiction first appeared in 1942 and poetry in 1945, but an unsigned editorial stressed in the closing year of the war “interest in democracy and social significance will continue to be the mark of theAntioch Review. ” After the war the political debates continued (”Why Communists Are Not of the Left”) yet there was a clear widening of focus with the inclusion of fiction by writers like Vern Sneider (author of the Teahouse of the August Moon) and more “social scientists” rather than political economists taking up issues. Robert Merton, David Riesman, and Daniel Bell had all appeared in the magazine by the end of 1951, and Riesman and Bell continued to contribute in the next decade with Riesman (on education) still appearing in the 1980s and Bell as recently as 2005. During the fifties poetry and fiction began to take (thanks to Nolan Miller) a more prominent place with writers like Philip Levine, Herb Gold, Sylvia Plath, and Alberta Turner beginning to appear alongside such social commentators as the philosopher James Rorty and James T. Farrell, the novelist. This mixture of poetry, fiction, and essay was most striking in 1957 when Farrell, Plath, Bennett Berger, Lewis Turco, and Clifford Geertz all published in the Review. Although the 1960s saw emphasis on issues and subjects relevant to academic interests (special issues on Shakespeare and the classical world), the magazine remained true to an eclectic approach rather than opting for dominant values. One might open the Antioch Review in those years before Woodstock and find a long translation of Ortega y Gassett’s “The Mission of the Librarian,” poetry by Mark Strand and Patricia Goedicke, and Rod Serling on his “Surface View of a Facade.” All appeared in a single issue in 1961.

1960–1976

Spring 1975

The Review had been edited in collective fashion during the early years and that practice continued into the 1960s with Paul Bixler taking an early editorial lead and Paul Rohmann (later director of the Kent State Press) assuming general control when the magazine came under the Antioch Press. By 1965 the journal had reached its first quarter-century, and Paul Bixler in a notable essay, “Quandaries of a Quarterly,” posed some questions about its past and future. “One wonders,” he wrote, “whether one man or a little group of men without liberal resources can make an impression these days or whether a small group can continue to sustain one previously established. Television has already taken over vast areas of human communication, which were once the province of print, and it may be expected to take more; still it is doubtful if it can or it should replace reading as a significant exercise. Publication itself appears more and more often as the result of large combinations of men and resources, and this is not simply the workings of monopoly or merger in giant associations for economic protection. . . in this new world, whether a small magazine of mature outlook but minimal resources can sustain itself still appears to be a personal problem.” Both the question and its solution still remain in today.

Fall & Winter 1975-76

The sixties saw a clear falling off of an emphasis on social analysis and a rise in the number of pages devoted to poetry and fiction. Joyce Carol Oates made her first appearance in 1966, William Trevor in 1967, and Quincy Troupe and Harley Mims the same year in a special “Watts Writers Workshop” edited by Budd Schulberg. An editorial shift occurred in 1969 with the appointment of a single editor and a diminution of direct board control in the affairs of the magazine. Under Laurence Grauman, Jr. the Review had a face-lift, aspired to be self-consciously controversial, topical, and a trend watcher if not setter. Some notable issues were produced and contemporary issues (the law, censorship) were aired. Daniel Ellsberg, Sidney Zion, James Aronson, Clay Felker, and Charles Newman all made appearances in the early seventies as the magazine both courted and created controversy.

As the Review rocketed along so did its primary backer, Antioch College, and both were on a collision course. During 1973 the college experienced both staff and student strikes, and its future and that of the Review seemed dim. As the result of a set of bizarre circumstances (including an effort to sell the journal through a “blind” ad in theNew York Review of Books), the editor was sacked and the college subsidy ended. An almost equally strange set of circumstances rescued the magazine with a substantial grant secured from the Ohio Board of Regents, which carried it while Paul Bixler (one of the original founders) reestablished its editorial integrity. Bixler, with the help of a new board and a supportive administration, saw the Review through several more financial crises.

1977–2001

Summer 1984

By the mid-seventies the new Antioch Review contained increasing amounts of fiction, had a contemporary look and feel (under art director David Battle) and a commitment to the essay as a form. By then the essay was taught in universities but few academics ventured to use it. When I became editor in 1977 the magazine had survived a major crisis in 1973, but still was on shaky financial ground. Its finances were tested again when the college’s subsidy was withdrawn briefly, and from 1979 to the present there has been improvement with the establishment of an endowment and the expansion of pages. Throughout the late seventies and eighties theReview’s fiction distinguished itself with numerous O.Henry or Best American Short Stories awards. Writers like T. Coraghessan Boyle, Gordon Lish, Maria Thomas, Sharon Stark, and Raymond Carver appeared, and essayists Elaine Showalter, Gerald Early, and David Riesman all contributed substantial (and topical) pieces. During this period Sandra McPherson and then David St. John acted as poetry editors in a separate section devoted to new work. Even though increasing numbers of well-known writers appeared in the Review, it continued to draw contributors from the “slush,” with two first stories winding up on “best” lists, and T.C. Boyle and the late Maria Thomas publishing here early in their careers. Issue and geographically oriented numbers appeared with greater frequency, and the focus shifted to other parts of the world with special volumes on China and the Argentine published in the late eighties.

Summer 1986

Magazines like the Review provide “good ground” for much of what is vital in our literary culture. They sustain writers in the early stages of their careers; they provide encouragement to mid-list writers and take on topics and subjects too lengthy or controversial for the commercial magazines. For certain readers (”who hath ears to hear”) they provide a vital link to creative work that enhances our humanity.

In our sixtieth anniversary volume (2001) there were several repeaters from the fiftieth anniversary number: Clifford Geertz, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Gordon Lish, Rick DeMarinis, and James Purdy. Geertz’s essay pays tribute to a founding editor of the Review, George Geiger, who died in 1998 at age 91. Another founding editor, Paul Bixler, passed away in 1991. During the 1990s a significant part of the Review was devoted to new writers who caught our attention “on the up bounce” (Arnold Gingrich’s phrase to describe what a literary magazine should be grasping for) and they included Daniel Harris, a wonderful critic and essayist, Edith Pearlman, a masterful short story stylist, and Aimee Bender, a bright and inventive young voice. And then there are those writers whose careers have skyrocketed in the last ten years, Ha Jin, Bret Lott and Alan Cheuse. All have been around for a while, but they have moved from the back of the bookstore (the literary magazine section) to the table up front.

Spring 1994

Since 1990 we have done special issues (several on poetry), but the “Jazz, Jazz, Jazz” issue in 1999 was a blockbuster. It outsold any issue in recent memory and requests for it came in from Jamaica, Japan, and elsewhere. There was a play by Ishmael Reed, essays by Michael Wood and James Campbell, both from Great Britain and both lovers of jazz.

Writers like Lore Segal, Sven Birkerts, Sallie Tisdale, S.J.D. Green (on a regular basis for the Review) have continued to contribute work. Essays that caught our reader’s attention during that period were: Robyn Sarah’s “Nine Days,” Jeffrey Hammond’s “Milton at the Bat,” Bruce Jackson’s “Stories People Tell” and Daniel Harris’s recent “The Writing Life” all struck a responsive chord among our readers.

The past decade saw our long-time poetry editor, David St. John; take a much-needed respite from his chores in 1996. Judith Hall who has put together two special poetry issues with more to come now guides poetry into the Review. Essays like this one celebrate several things: one, our survival (our fiftieth anthology was titled the “Survival of the Imagination”), our persistence despite obstacles (we publish without a significant subsidy and rely on the sympathy of our friends), our continuing commitment to serve our readers and our authors and to encourage others to publish the “best words in the best order.” Over the years–to quote Gordon Lish–we have tried to be a magazine that “freely serves the mind and heart of the free reader.”

2002–present

In 2011 we celebrated our seventieth year of continuous publishing with a 400-page issue that brought together the “best” work of the previous decade. We opened this retrospective with a personal response to 9/11 by Stephen Jay Gould, whose piece “Ground Zero” was among his last, and we closed the number with a poem by Susan Wheeler. In between there was more than a Whitman’s sampler of goodies: repeaters from our sixtieth-anniversary include Aimee Bender, Rick DeMarinis, Clifford Geertz, Daniel Harris, David Lehman, Gordon Lish, Jacqueline Osherow, Edith Pearlman, Sallie Tisdale, Susan Wheeler; newcomers such as Nathan Oates and William Giraldi; translators from here and abroad like Ralph Angel, Robert Conard, and John Penuel.

Summer 2005

There were essays by world-class figures like our Advisory Board member Daniel Bell and the head of the British Library Neil MacGregor. During that decade we were finalists for the National Magazine Awards in 2009, 2010 and 2011. The masthead has had just three major changes during the past fourteen years, first with Muriel Keyes carrying a large administrative burden (as assistant editor) that involved making sure the first readers (all ten of them) log in and out the thousands of manuscripts we get; that our interns work; that the bills get paid; and, most important, that we treat our authors work with respect. Muriel retired in June 2015 and Christina Check continued her good work as our Managing Editor until 2016. In 2013 Grace Curtis joined our staff to assist with marketing and social media contacts. Our designer, David Battle, continues his brilliant work despite his quarterly lament that he can’t “do anything” with a particular issue and then does it (see the covers). Jane Baker makes sure that what we publish is in the King’s English and error proof.

Our “Doppelganger Moment” came with the Winter 2013 number with an electronic version available through JSTOR, the highly regarded nonprofit organization headquartered in New York that has specialized in providing libraries all over the world with digitized versions of periodicals (particularly those with long runs like the Antioch Review). Recently they have branched out and now provide digitals editions to individuals, corporations, and other entities that want an electronic version of a current magazine. We have opted to go down the doppelganger road with our print version as before, but now our shadow is available for libraries and individuals who prefer to get it either way. We are now “double walkers.

75th Anniversary Issues