In the wake of the Women’s March and the #MeToo movement, Antioch College’s SOPP has come to the forefront as a way forward in the pursuit of a culture free from sexual violence.

It’s no surprise that Antioch College’s trailblazing Sexual Offense Prevention Policy (SOPP) has been in the news lately. Our national—and even international—conversations about consent, sexual misconduct, and sexual assault point to the same conclusion that a group of women on campus came to in 1990: to create a culture free from sexual violence, you have to get radical and come up with an unconventional solution. Dismantling old systems requires new tools.

Implementing a progressive reform is never easy, and the SOPP was not well-received in the ’90s outside of Antioch, nor universally within. Despite that, students kept pushing forward. With each generation, the social issues students struggling with change, and policies like the SOPP grow and change with the students. Antioch started this conversation in 1850. From equal pay for men and women of the faculty to educational opportunities for women in all majors in the 1850s, to the reputation for the College as a source of activism and social justice in the 1950s and 1960s, the College continues to be on the leading edge of social change. The rest of the world finally catches up.

The SOPP is just one example of why we need Antioch College now more than ever, because Antioch allows students to broaden their perceptions and struggle with big issues. There’s space here to create changemakers who will lead society forward. Currently students are creating new systems for community governance and implementing new policies for caregivers on campus. They are examining further issues of personal space and consent. They are owning their education and engaging in the world through Co-op. When they graduate, Antiochians carry that changemaking spirit with them. Alumni applications to the Winning Victories Grant (the recipients of which will be announced at Reunion 2018) demonstrate how many alumni— of all generations—are making inspiring transformations in their communities.

Reaction to the media coverage of the SOPP, Antioch College, and the revolutionary women who built the landmark policy has been widespread. Below are reactions from alumni and more.

Even when a group of students seeking an effective sexual offense policy has the full support of the president, as was the case at Antioch, it is a difficult process. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the board of trustees to make sure that such a policy exists. This requires a college community to state explicitly that it will no longer condone centuries-old practices growing out of the parallel myths that “boys will be boys” and “girls ask for it.”

From my years at Antioch, 1962–1967, I have no memory of sexual offenses, either occurring or being discussed on campus. I don’t doubt that both happened, but in that period, war and racism seemed more central to our political concerns. Sexual relationships, on campus and off, during Co-op jobs, were evolving, often at the forefront of the cultural revolution of the ’60s, i.e., freer than many from the constraints of the ‘Father Knows Best’ culture of the 1950s, but part of the struggle to find new patterns of acceptable gender interaction as old ones were being discarded.

While the exploration of gender relationships and the conflicts that would eventually lead to SOPP were being thrashed out at home, my first serious confrontation over those issues took place in France during my Co-op year abroad. Having brought with me fairly traditional gender attitudes from the rural area of my childhood, I was soon confronted by French women who were some years ahead of my American peers in challenging such norms. They were fighting to free themselves from gender-biased laws even more constraining than those in the U.S.

That awakening to gender issues in France, served me well when I returned home, and within a year moved on from Yellow Springs to Palo Alto (Stanford) in the midst of the anti-war movement and the sexual ferment of the 1967 “Summer of Love.” As part of SDS, and then the April 3rd Movement, our efforts to mobilize students against the university’s contributions to the war had to deal with gender issues because militant groups in those days included both men and women and second-wave feminism was emerging across the nation. Basically, we confronted, on a regular basis, all of the gender issues that have preoccupied and motivated ours and subsequent generations. “In the four decades that followed— as a professor in three different universities—I’ve watched all those issues that we confronted being fought out over and over, sometimes within groups, sometimes between groups. So, when I heard about SOPP at Antioch, I was not surprised, not by the problem addressed, nor by it being Antiochians who were on the cutting edge of dealing with it. La lotta continua.

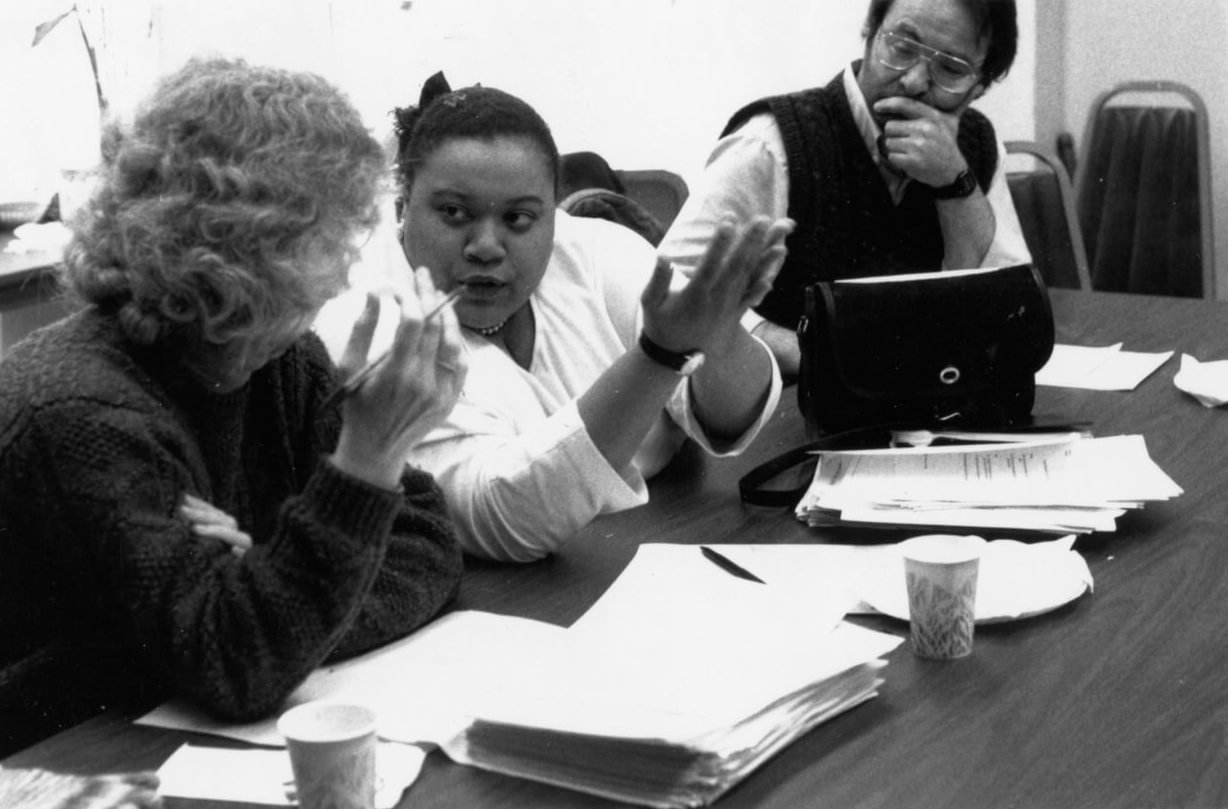

Community Manager Hope Harkins ’91 (center) at a 1990 AdCil (Administrative Council) meeting.

Antioch and the SOPP definitely changed and helped define what my ideas are around consent. It wasn’t until my final Co-op in Boston when I really engaged with other communities (kink, fetish, sex positive, and polya) that I became more engaged. Consent became more specific in how it can be applied in these communities. I learned how full negotiation in the kink and fetish community was even more specific and full of detail compared to what the SOPP goes over.

In essence, Antioch and the SOPP gave me a good starting-off point concerning consent education. I feel like we can definitely go deeper into conversations about engaging in intimacy with other individuals and the SOPP is a platform to do so.

All the recognition feels like a kind of vindication for the good old “Toxic ’90s-Era Antioch” and the fights we were picking back then—which even many on the left would disparage as indulgent ‘identity politics’ and ‘PC argle-bargle.’ And I’ve been struck, thinking back on that time, by the degree to which that attitude infiltrated our internal dialogue as an inter-generational College community. We were plagued by self-doubt, represented as we were in the culture as weirdo snot-nosed brats and performative non-conformists. Fast forward a quarter-century, and the College is still this fierce and fragile little thing living a precarious existence in a hostile world, but the culture has caught up with us on a number of fronts.

At Antioch, Bob Devine ’67 and Warren Watson introduced me to the Freudian concept of the “return of the repressed,” the process by which societal traumas like our dirty wars at home and abroad may reemerge as literary monsters, cinematic zombies, and the like. The popular recognition of rape culture, examination of systematic white supremacism, and rejection of homophobia (and even transphobia) feel like a benevolent return of the repressed to me, a raising up of stuff long buried under the placid surface of a million pre-Internet SNL skits and New Republic takes. And I’m so grateful to all those who did the spiritually taxing work of digging this junk up, from Act Up to the Womyn of Antioch to Black Lives Matter and beyond.

The student “Womyn of Antioch” pictured in 1991. Steffi Hoffman, Idella Burmester ’90, Drea Brown ’92, Bethany Saltman ’92, Juliet Brown ’93, and Christelle Evans ’94.

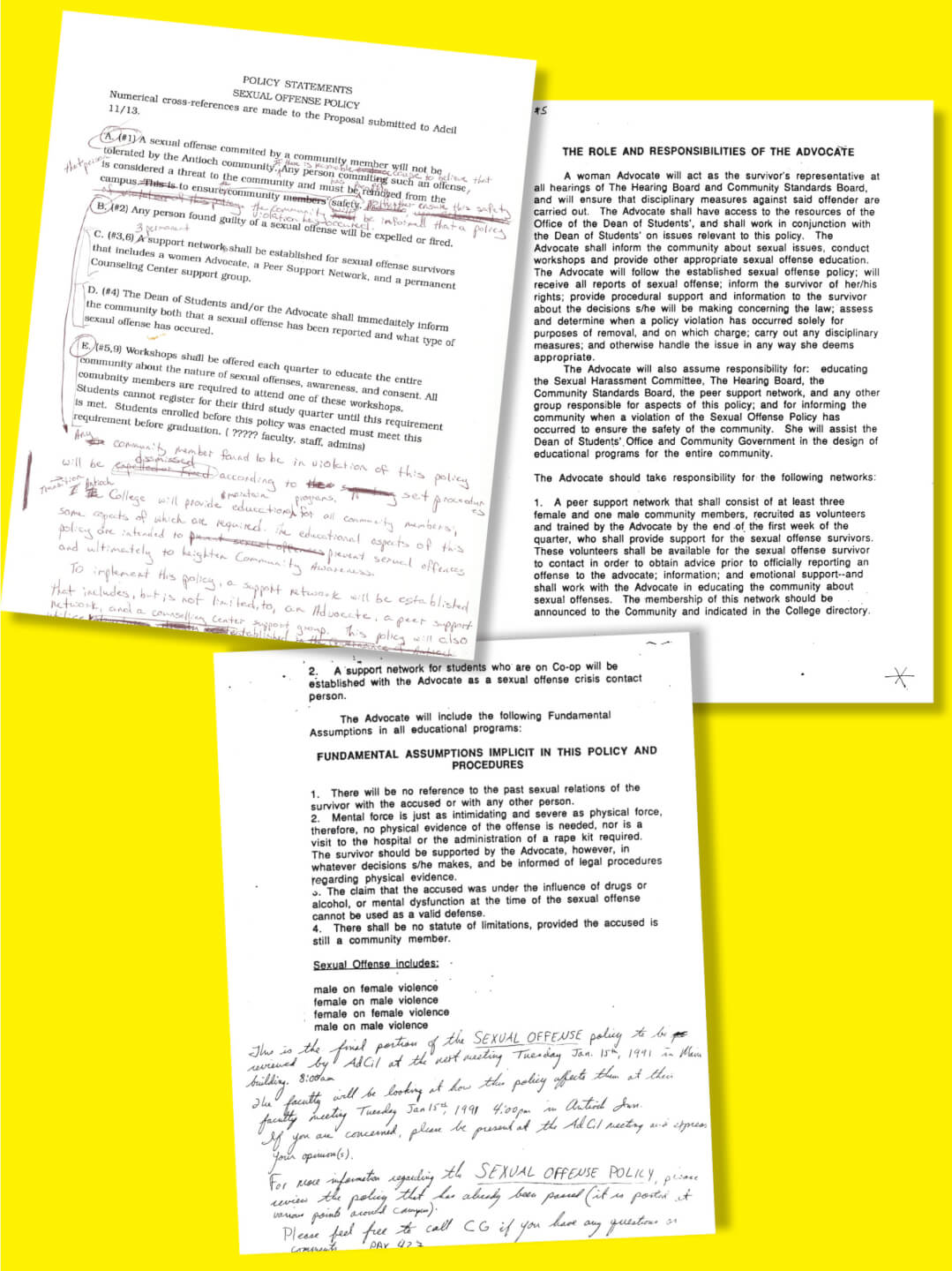

The first SOP[P] (originally the SOP: Sexual Offense Policy; later changed to SOPP: Sexual Offense Prevention Policy) is deliberated at a November 1990 AdCil meeting.

The SOPP could only emerge from a place like Antioch College where students are encouraged to think beyond themselves and to push the envelope on academic and social issues. It is instilled in us to “win victories for humanity.”

Antioch’s Community Governance model was key to our success in creating the policy and programs that shaped the SOPP. It gave students a vehicle to go beyond the demonstration phase of our activism to actual policy and program development. Demonstrations are important for bringing people together and calling attention to issues like sexual violence, but policy development affects change for generations to come.

I am very proud of the work of The Womyn of Antioch and those faculty, staff, students, and administrators serving in Community Government roles. We invented language to articulate and define what has come to be known as “active” or “affirmative consent.”

Skills like group facilitation, policy and program development, consensus building, and negotiation were just a few of the things I learned from my experience with the SOPP.

My work around affirmative consent did not stop with Antioch either. Over the years I’ve been involved with other consent discussions including work a few years ago on a Code of Conduct that moves the idea of consent into the realm of behavioral standards. This Code of Conduct calls out abusive behaviors that are not tolerated at events or within a community. I see this as a continuation of our work on the SOP[P].

It’s thrilling to see the rest of the country catch up with Antioch in the early ’90s. Antioch has always been a wonderful place, and this is just another example of the way it functions as an incubator for social change and justice.

I suspect that issues surrounding gender identity and pronouns will be one of the next social issues that the country will need to grapple with.

Published in the Spring 2018 issue of The Antiochian, a magazine for alumni and friends of Antioch College.