Admission Blog

A Monday [Part 1]

8:12 am

I wake up to my phone playing—very loudly, and seemingly of its own volition—the first track off Fiona Apple’s (stellar) new LP, Fetch the Bolt Cutters. It’s called “I Want You to Love Me,” and is, like all my favorite Fiona Apple songs, delicate and ethereal and just totally pummeling.[1] It begins with a brisk, elliptical piano part which sounds, to me, like nothing more than dogged optimism itself: like piloting a very small craft into very strong headwinds, and doing it with a smile.

_________________________

1. If this sounds like a paradoxical description to you, I suspect it’s because you haven’t heard Fiona Apple’s work before. You need to change that. Trust me. Listen to “I Want You to Love Me,” and then listen to “Carrion,” the last track of Apple’s first album, 1996’s Tidal. Once you have, call me so we can talk about Fiona Apple. My number is 614-531-5276, and as this post will make clear, I’m free pretty much whenever.

My alarm’s set for 9:00 am, but another hour of sleep hardly seems worth sacrificing the feeling of waking up to this.

It occurs to me, as I’m brushing my teeth, that this is just the sort of thing Patty Nally, Antioch’s Executive Chef, would play in Birch Kitchen during breakfast.

It’s been my experience that chefs all have great taste in music. All the chefs I know do, anyway, though I’m not sure why. I know, after a restaurant closes for service, the kitchen staff sticks around for about two hours after to clean up everything and get ready for the next day; and I know, during this time, someone usually pipes a mix through the speakers. But why these mixes are all expertly curated? Unclear.[2]

_________________________

2. Conceivably, it’s that a refined gustatory sensibility and a refined aesthetic sensibility are exactly the same thing, only employing different senses. That’s a good-enough explanation.

Patty is, in this respect, no different than the other chefs I know. (Though, having had her blueberry grilled cheese sandwich, I can say she is, in several different respects, qualitatively better than the other chefs I know.) If you eat in Birch Kitchen on a shift Patty works, without fail, it’ll be to the sound of an excellent musician’s best work: Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville, Galaxie 500’s On Fire, Lauryn Hill’s Miseducation of… etc etc.

This is the first manifestation of Antioch’s absence: I suddenly miss Birch Kitchen’s breakfasts—a lot. Though I usually only stop in about once or twice a quarter, I’m always glad when I do: The bustle of activity in the open kitchen space is bracing when you’re still half-asleep. There’s something, I think, about being in a brightly-lit room filled with people who are awake at an hour when most people aren’t—something bracing, something bolstering. It makes me feel at home in the world, and eminently capable of facing whatever the day ahead has in store. Like: If Lord Cardigan had taken his light cavalry to a crowded Waffle House at about 5:00 am, bought each of his men a cup of coffee, and let them sit for about an hour before mounting their horses, the Charge at Balaclava might have gone quite differently. Such is the restorative power of a good breakfast among others enjoying the same. And the coffee at Birch is better than the coffee at Waffle House.

But I’m alone and Birch is closed, and Waffle House is, too. I will, I realize, have to do the best with what I have.

8:35 am

Christ.

Christ.

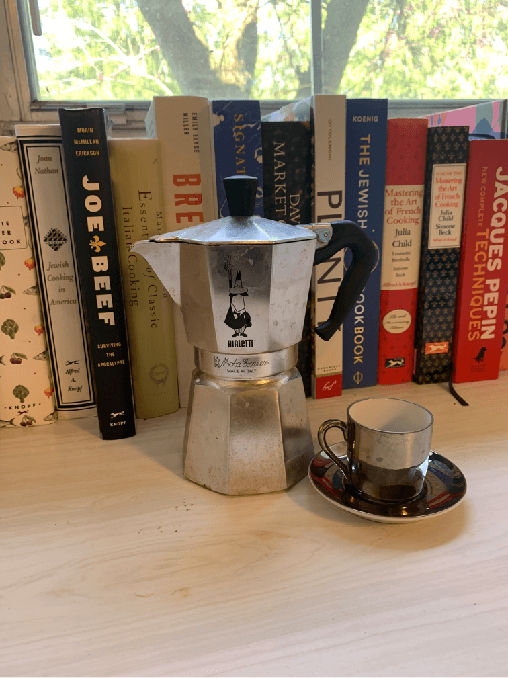

This is my coffee pot. I hate it. I bought it because I am a total dupe, and now I hate it. The tidy art deco lines, the elegant script spelling out the words ‘Moka Express,’ the look of sleepy resignation in the cartoon logo’s eyes—all these things informed my purchase, yet not once did I bother to wonder if the thing would actually make good coffee. Which: No. No, it would not. What it would do is make the sourest, bitterest coffee I’ve ever tasted, and not very much of it, either—like, three shots of espresso per pot, maybe. Today, I throw them back in rapid succession, with the grim sufferance of a diabetic injecting himself with insulin. At least the cup and saucer lend the whole, dismal ordeal an air of dignity.

I wouldn’t have used them before the quarantine, I realize. The cup and saucer: never would have even thought of using them. Something about being housebound has impelled me to pay attention to various domestic rituals I had, before, flouted, provided I was aware of them at all. I find myself doing things like sweeping my apartment’s foyer and airing its rugs with a kind of assiduous care that astonishes me. I’m living—shit: I’m living intentionally.

9:03 am

When I first came to Antioch, many of my peers—and my professors, too—were interested in what they called ‘intentional living;’ and though I wasn’t sure quite what they meant by this, I was pretty certain I hated it.

As best I could tell, intentional living meant making tea with nettles you’d harvested yourself. It meant darning socks you should have thrown away years earlier. It meant waking up at 4:00 am to spend five hours foraging for a couple etiolated mushrooms instead of going to Whole Foods and buying half a pound of gorgeous wood-ears like an actual fucking person. It meant eating meals that consisted of nothing but sauerkraut you’d fermented yourself, in an apartment reeking of various lactobacilli. It meant reading Wendell Berry when you could read literally any other author ever published. It wasn’t for me.

In the course of my four years at Antioch, I came to understand the sundry ways in which intentional living was a worthy undertaking. It was sustainable and ethical, grounding and edifying. It resulted not just in presence-of-mind, but sometimes, maybe in peace-of-it, too. None of which meant I wanted anything to do with such things. I regarded Antioch’s leading practitioners of intentional living—Beth Bridgeman comes to mind—with the same detached, abstract admiration I afforded dedicated philatelists and accomplished pool hustlers.

And now I’m baking my own bread every goddamn day. If that isn’t intentional, what is? I want to find Beth Bridgeman, and say ‘Look at me now!’ I also want to find her and ask her to look at my dough, and tell me if it seems OK. I’m staring warily down at it, now, and it looks—well, it looks doughy. I’m new to this whole baking thing. I’m not sure I even understand what gluten is.

I sigh, punch down the dough, and put a dishtowel over its bowl. Two hours from now, I’ll tip it into a dutch oven, let it cook (covered) for about 45 minutes, and hope for the best.

Which other aspects of Antioch that I find terminally goofy, puzzling, or just plain dumb will make sense to me in the future, I wonder. Surely, there’ll be more. Will I, a month or a year or a decade from now, be making my own soap? Enjoying the work of Judith Butler? What?

No, I tell myself. Antioch still has a lot more to teach you, but you will never, ever enjoy the work of Judith Butler. I smile.

Self-affirmations, folks: They really work!

11:40 am

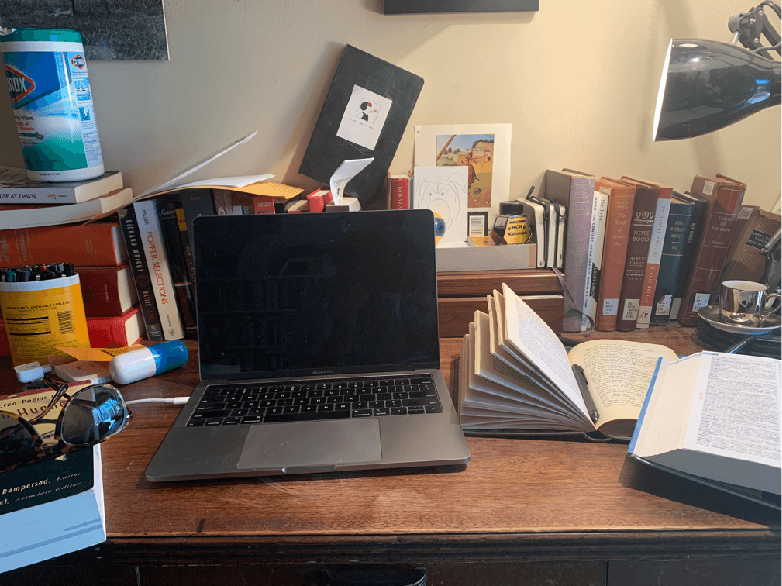

For the past two-and-a-half hours, I’ve been sitting at the desk that has, since the quarantine, served as my Antioch surrogate. My desk is my McGregor in that I attend classes here, via Zoom, is my Olive Kettering Library in that the books I’ve read for and cited in my thesis are all sitting on it, and it’s my Main Hall in that it’d be quite a formidable presence if only someone took better care of it. Here’s what it looks like:

The Clorox wipes are a gift from my parents, and arrived at my door in a large, padded envelope a couple days ago. So far, I’ve only managed to use them to wipe down the surface of my desk each morning, before getting to work. My mother tells me this isn’t the way to use them—she says they’re to wipe down groceries—but I can’t imagine using them to this end will make me feel as good as my new ablutionary practice.[3]

_________________________

3. “Who wants to feel well if you don’t feel good?” I asked my mother, after she described my use of the wipes as ‘completely ridiculous.’

“Everyone!” she crowed, her voice cracking in frustration. “You can’t feel good when you’re dead!”

“Metaphysical Mom,” I said. “Groovy.”

“Would you please just wipe down your groceries?”

I told her I’d seriously consider what she’d said, and would render a verdict in due time. What I didn’t tell her was that, until our conversation, I’d been dousing my groceries in isopropyl alcohol and scouring them with an old toothbrush. The concept of using Clorox wipes for this purpose had simply never occurred to me. While we were still on the phone, I started polishing a couple blood oranges with one of the wipes, and I haven’t looked back since. What once took me an hour now takes about ten minutes. Of course, I still wipe off my desk each morning, but I also took my mother’s advice. Which, I realize now, I still haven’t told her. Mom, I’m sorry. I don’t know why I’m like this, either.

Presently, I’m working on translating one of my favorite books, Romain Gary’s 1960 memoir Promesse de l’aube, from French into English. I have been all morning. It’s for an independent study I’m taking with Cary Campbell, Antioch’s Assistant Professor of French Language and Culture. I’m the course’s only student, I have only one assignment: translate Gary’s book, in its entirety, by the quarter’s end.

I’ll get into the specifics of the course in a later post—one I’ll probably publish next week.[4] For now, I’d just like to share with you the sentence I’ve just translated. In the original French, it reads, «Souvent, en rentrant du bureau, j’allume un cigare, je m’assieds dans un fauteuil, et j’attends que quelqu’un vienne s’occuper de moi,» Here it is in English, literal and leaden in a way (I hope) it won’t be in later drafts, but accurate enough: “Oftentimes, I get home from the office, light a cigar, sit in an armchair, and wait for someone to come do something about me.”

If anyone read my last post—the one about memes—and was wondering: That’s my idea of relatable content.

_________________________

4. I’ll also discuss why independent studies as Antioch conducts them are so great, both because this is something I actually believe, and because Antioch’s paying me to write these posts: I’m a student worker in the comms office. While none of my bosses have ever told me to shill for Antioch, and while I know they’d never dream of exercising prior restraint, I also know they want me to. They’re not gonna say it, but they do. And, honestly? I believe in the product I’m slinging, here.

11:51 am:

OH GODDAMMIT THE BREAD OH GOD HOW LONG HAS IT EVEN—THIS QUARANTINE IS SUCH BULLSHIT. WHY AM I EVEN BAKING BREAD? JESUS CHRIST ALMIGH—

11:53 am:

OK. I see what’s happened, here.

I started out pretty well, in that I put the bread in the oven. That’s where it’s supposed to go! It’s when I closed the oven door that things went sideways: instead of remembering that it was in there, did the opposite of that, which is completely forgot about it. That was—well, it was at some point in the recent past. An hour ago? Sometime in March? Who’s to say? It was the past, and that’s all I know: a time before my apartment smelled as it does now, which is like a benign version of hell, where the mediocre are condemned to an eternity of light singing. The Dutch oven in which I baked my bread is now resting my stovetop, radiating heat and vague menace.

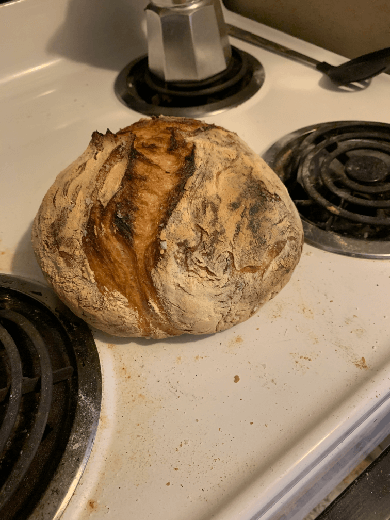

I remove the pot’s lid and brace myself for what’s beneath it: I’m imagining something ossified, something torrefied, something that’ll blacken my fingers, warp my knives, and plink tunelessly like cheap ceramic when it his the cutting board. Instead, I see this:

This should not have happened. This was a fluke. Anything I did right I did accidentally; everything I did wrong I did in blithe certainty of its rectitude. I can’t explain it. I can only chew—first with slow, wary circumspection, and then eventually with relish. I don’t really know what to say. Small mercies exist in even the most merciless times—even in times of plague. The way to respond to them probably isn’t to shout something triumphant and mildly imprecatory at an absent-and-beloved member of the Antioch community, but again: Who’s to say? Haven’t we all, in some sense, shouted, “HOW DO YOU LIKE ME NOW, BETH? THERE’S A NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN!” before?

It’s really very good bread.

[TO BE CONTINUED.]

About Ben Z. ’20

Ben is a member of the class of 2020.

He’s studying literature.

He enjoys a good club sandwich, and once got a chicken elected to Comcil.

Storytelling

Choose Your Character

Safe, On Campus

Entering the final weeks of fall quarter, no Covid-19 cases on campus

Antioch College Admission

Discover