A ‘hidden immigrant’ attempts to explain the logic of America to her Canadian co-patriots

A version of the following was originally published in The Monitor, the bimonthly policy and current affairs magazine of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Twelve years ago, I made the difficult decision to leave the United States, the country of my birth, for Canada, a land that, at the time, I assumed was filled with moose, hockey, and—the real draw—national health care.

Ironically, HOPE was really the feeling du jour back then in America, especially in Chicago—my home for over a decade. Senator Obama’s campaign motto was woven into speeches, plastered on walls, emblazoned on an impressive wardrobe of T-shirts. For me, HOPE was what drove me to put my cats on a plane, my books in a shipping crate, and pack everything else into my car for the drive to Vancouver. As an alum of Antioch College, I was used to packing up and moving and adapting…years of Co-ops had taught me well—and I was ready to start a life I truly believed would be better for me and my future children. But, to be clear, it was a HOPE weighed down by frustration and resignation.

On New Year’s Eve 2008, the day that my Canadian immigration paperwork arrived, I wrote a letter to Obama, then president-elect, explaining why I was choosing to leave the U.S. It read in part:

I need a government that will invest in me and my education. I need to be in a country that recognizes health care as a human right and that will allow either parental paid time off to raise a child for the first year or provide affordable state-subsidized quality child care. We’re just not there yet, and I don’t know if—or when—we will be…. I want to live, prosper, and be free, and I want my children to grow up believing this is the norm.

On the eve of another U.S. election, my letter looks more prescient than overly pessimistic. Clichés about hindsight aside, the Obama decade’s list of policy could-have-beens is long, and a country of HOPE is now steeped in and driven by FEAR. Fear of the pandemic (or masks). Fear of nationalism and white supremacy (or the Black Lives Matter movement). Fear of unravelling democracy, and unhinged demagogy. Fear of each other. Much of that fear has been stoked by our sitting president, the former game show host Donald Trump, who appears to thrive on it.

But I digress, as we so easily do around Trump. I set out to write about my experience of leaving the United States and settling in Canada.

As I learned in my critical race theory course in my second year of Antioch, sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (1986) terms people who are marked—or not “the (presumed) norm”—in a particular field as “outsiders within.” She argues that people within this position can often more clearly see the machinations of power, justice, and injustice because they are NOT benefiting from the status quo. In her original piece she was referring to Black female domestics working in white family homes as well as to herself as a Black female sociologist in a white, male-dominated field, but her ideas go far beyond that. I believe that in some ways, I am a “hidden” immigrant, which also posits me as an outsider-within when reflecting on both Canadian and American societies (note plural).

I am white (and there is the problematic misconception that Canadians are white and immigrants are not) and English is my first language. But I am also a member of a religious and cultural minority who did not grow up in Canada.

When I arrived here 12 years ago, the medical, taxation, and postal systems were literally foreign to me and I made a lot of assumptions and mistakes interacting with them. (I have no family here, so I was heavily reliant on these public institutions to guide me in all aspects of my life.) For the first year or so, the “9” on my social insurance number—indicating temporary residency—all but ensured I would not get hired. For many years I could not vote. And since most people I met assumed I was culturally Canadian, my directness was constantly read as rude, and my lack of familiarity with Raffi, The Kids in the Hall, or curling a bit unnerving.

When people find out I am in fact American-born, I often find myself trying to explain to my Canadian co-patriots that there is a logic behind what is sometimes interpreted as collective madness south of the border. From an early age, Americans are raised on a sick cocktail of meritocracy and American exceptionalism that scoffs at the idea of social safety nets and those who might need them. This is the mentality of desperation, of internalized self-reliance (a close cousin of shame), and it has a direct effect on policy and politics.

The U.S. socioeconomic and political system denies, and in fact belittles, the notion of a social safety net. In my 30 years in America, 15 of them working, I knew what it felt like to not feel you can afford to go to the doctor, to watch an epileptic mother be denied health care because of her pre-existing conditions. As I wrote in my parting letter to Obama, “I was tired of begging for reduced rates with doctors. Tired of having no workers’ compensation…. Tired of not having the basic rights of health care and parental leave guaranteed to much of the industrial world.”

I remember calculating what taking a single sick day might mean for my job, and thus my health insurance plan. I can imagine how it might feel to get a positive COVID test knowing both medical care and time off to self-isolate are not viable options. I can understand what it means to fear going to the doctor because you are undocumented and not sure who you can trust—doctor, employer, neighbour—with your immigration status. I understand what it means to really have no one to rely on but yourself.

Like frogs in a slowly boiling pot of water, you become so used to the rising stress you believe it is the only way.

This personal suffering under the mythology of meritocracy is almost a patriotic duty in the U.S. I was raised to believe I was a part of the fabric of the United States, and that with such belonging came both rights and responsibilities. The United States had enabled my grandparents, as Jews, to live a life of safety and escape persecution, indeed genocide, when no other country in the world would do so. This part of our history—the persecution, perseverance, and belief in American exceptionalism—was, and continues to be, a constant refrain in my life. The flag still flies proudly on my mother’s door.

Patriotism runs deep in my family. Both of my grandfathers served in the U.S. Army even though neither was fluent in English at the time. But for me, patriotism does not mean “my country right or wrong.” It does not mean being blind to reality. Rather, as a beneficiary to what would now be referred to as political asylum, I was raised with an obligation to stand up when things were not right and to fight and work to make it better. This was, and is, my definition of what it means to be patriotic: continuously making critical contributions to our broader society.

But by the time I turned 30, I no longer knew how to juggle my sense of political and social responsibility with my personal goals of becoming a mother. I was frustrated and I felt like a fraud. I was living and working and indeed contributing to a system I did not believe in and that I knew was dishonest and unsustainable. I was constantly internalizing my “failures” of balancing family, professionalism, and activism. Although I am the first to admit my flaws, the problems with the U.S. economic and social system would not be overcome in time to fix the disconnect that was building inside of me.

My current life would not be possible in the United States. But it has not been easy, either. In the 12 years I have lived in Canada, I have never worked a permanent job. Child care costs over $7,000 a year (for one child) and for many years I paid my dentist, eyeglasses, and counsellor out of pocket because I had no extended health care. That said, as a white, well-educated, English-speaking person, Canada has treated me well. I completed my doctoral work at a respected Canadian institution (paid for by the Canadian government) and received my citizenship in 2017.

In 2019, I gave birth to my daughter without paying a dime.

I have often wondered what I can give back to Canada—a colonial country that I had the privilege, not the right, to join. Although I live in Winnipeg now, when I emigrated in August 2009 it was to unceded lands in British Columbia. My emigration was therefore legal, but not necessarily right, as it was the Queen of England, not the original peoples of the land, who are still very much there—Musqueam, Tsleil’waututh, and Squamish nations—who granted me stay. My formal education, English language, and profession—my unmarked privilege—granted me full participation in the colonial state.

For many years now, I have designed and taught courses on social inequalities, migration, and human rights institutions (Canadian and international) at world-ranking Canadian universities and have written many journalistic and academic pieces covering issues of race, migration and activism. I like to think my position as “a hidden immigrant” has enriched this work. I feel it has certainly allowed me to see the creeping forces of nationalism, meritocratic ideology, anti-intellectualism and fear as it manifests north of the 49th.

Canada is not exactly the country I thought it was when I wrote my farewell letter to Obama. It is because of my recognition of this fact, my privilege, and my responsibility, that I now work at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and teach and research on human rights (both domestic and international). But I do not forget where I come from and I do not take what I have for granted. I will always keep both in mind as I use my skills and experiences—as an immigrant, an activist-academic, a mother—to contribute to the betterment of both of the countries I choose to call home.

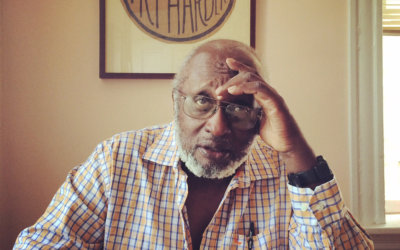

About Shayna Plaut ’00

The work of Dr. Shayna Plaut ’00 sits at the intersection of academia, journalism, and advocacy. She is interested in how people represent themselves in their own media, with a particular interest in peoples who do not fit neatly within the traditional notions of the nation-state. Shayna has served as a consultant for numerous NGOs including the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. She is the Human Rights Editor for Praxis Center—an online resource center for artists, academics, and activists, as well as people who identify as all three—and the Research Manager for Strangers at Home, a project of the Global Reporting Centre. Shayna has designed and taught a wide array of courses on human rights including at Simon Fraser University, Columbia College Chicago, and the Graduate School for Journalism at University of British Columbia. Currently, she is writing a book on how migrants are challenging and changing immigration policy through discourse in Europe.

The work of Dr. Shayna Plaut ’00 sits at the intersection of academia, journalism, and advocacy. She is interested in how people represent themselves in their own media, with a particular interest in peoples who do not fit neatly within the traditional notions of the nation-state. Shayna has served as a consultant for numerous NGOs including the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. She is the Human Rights Editor for Praxis Center—an online resource center for artists, academics, and activists, as well as people who identify as all three—and the Research Manager for Strangers at Home, a project of the Global Reporting Centre. Shayna has designed and taught a wide array of courses on human rights including at Simon Fraser University, Columbia College Chicago, and the Graduate School for Journalism at University of British Columbia. Currently, she is writing a book on how migrants are challenging and changing immigration policy through discourse in Europe.

Shayna says, “My start in teaching came from my education at Antioch College. It was there that I learned, through modeling, the importance of praxis and context. To really understand how to make change, one needed to understand the multiple roots of the problems from a variety of theories, disciplines, and lenses. It was also very clear that no situation was devoid of context—economic, political, social, cultural—and that this was filtered through one’s race, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability, language, and nationality. These were not add-ons in classes—this embrace of critical positionality was the cornerstone of my Antioch education and has deeply influenced my teaching, writing, research, and activism. This approach can help us better understand our current realities of how COVID—and all that comes with it: economic uncertainty, travel bans, opioid overdoses, domestic violence/intimate partner violence—is experienced so very differently throughout the U.S. and Canada. I am proud to identify as an activist-academic and I credit Antioch for recognizing the power, if loneliness, in that position.”

Published in the Fall 2020 issue of The Antiochian, a magazine for alumni and friends of Antioch College.